During a freeze event in 2010 in the Dover area of Florida, ground water levels dropped to record-setting lows as farmers pumped water to irrigate their plants for protection from the cold. More than 110 sinkholes formed, destroying homes, roads and sections of cultivated areas.

(Photo by Ann Tihansky, USGS)

In Guatemala, a massive sinkhole opens up in a downtown district, swallowing a three-story building. In Florida, part of a residence collapses into a 30-foot wide sinkhole, killing a 36-year old man. In Louisiana, a 26-acre sinkhole creates a chemical lake that threatens wetlands, wildlife and nearby communities.

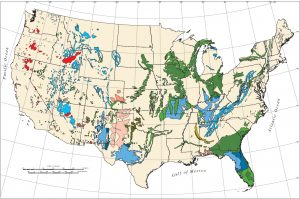

What are sinkholes, and what causes them to form? According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS) sinkholes are areas of ground that have no natural external surface drainage. When such areas are underlain by rock types that are susceptible to dissolution in water, circulating groundwater can result in the development of underground cavities. These types of rocks, known as evaporates, underlie 35 to 40 percent of the United States, and it is estimated that 20 percent of land area in the United States is susceptible to sinkhole formation. Common evaporates include limestone, carbonate rock, and salt beds. When these rocks lie near the surface, the size of the cavities can progress to the point that the thickness of the overlaying material is not strong enough to support itself, and the sides and roof of the cavity cave in, creating a sinkhole. The collapse can be dramatic and catastrophic, as the ground surface above the cavity often remains intact with no visual outward signs that a collapse is imminent. When many of an area’s landforms are created by dissolution of rock, the landscape is often referred to as “Karst” topography. Karst terrain is characterized by sinkholes, cavern systems, and disappearing streams and springs. In the United States, the most damage related to sinkholes tends to occur in Florida, Texas, Alabama, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Pennsylvania. In Florida alone, there are an estimated 15,000 sinkholes.

Types of Sinkholes

Sinkholes are generally categorized into three types: dissolution sinkholes, cover-subsidence sinkholes, and cover-collapse sinkholes.

Dissolution sinkholes occur at the ground surface where bedrock is exposed or is very shallow, and result from rainfall and surface water percolating through the bedrock’s joints and fractures. Dissolved carbonate rock is transported in the water, leading to the formation of a depression. The depression in turn focuses the surface drainage, accelerating the dissolution process.

Cover-subsidence sinkholes develop at depth, where the bedrock is overlain by permeable sediments that consist largely of sand. Surface drainage infiltrates through the overlying sediments and through joints or fractures in the bedrock. As the bedrock is dissolved, the granular sediments migrate into the resulting spaces, creating a depression in the ground surface. Cover-subsidence sinkholes tend to develop gradually, and go undetected for long periods of time.

In contrast, cover-collapse sinkholes tend to progress rapidly; it is this type of sinkhole that often results in catastrophic consequences. Cover-collapse sinkholes occur when overburden soils contain a high percentage of clay. They form in the same manner as cover-subsidence sinkholes; however, the cohesive nature of the clay allows a “bridge” to form above the enlarging cavity. Eventually the bridge is breached, resulting in a sudden and often disastrous event.

Areas of greatest sinkhole susceptibility are shown in blue and green. Areas of karst topography are shown in red and pink. Yellow indicates areas of low sinkhole susceptibility.

(Map by USGS.)

Human Influence on Sinkhole Formation

Sinkhole formation can be instigated or accelerated by human activities. New sinkholes have been linked to land-use practices such as groundwater pumping, which can disrupt groundwater levels and upset the delicate balance between and underground cavity and the surrounding earth materials. Sinkholes can also form when natural drainage patterns are altered by development, or when the surface topography is changed, such as when water storage ponds are constructed. Mining operations are also linked to sinkholes. Mining of a salt deposit is believed to be responsible for the giant 26-acre sinkhole in Bayou Corne, Louisiana. A 750-foot deep cavern, which developed as the salt was mined, extends into underlying natural oil reservoir. Oil and toxic gases, including explosive methane and hydrogen sulfide, formed a “chemical lake” within the sinkhole. A system of levees built in an attempt to protect adjacent wetlands and waterways deteriorated due to continued seismic activity, raising concerns from regulators and residents of Bayou Corne. On publication dubbed the situation “the biggest ongoing disaster in the United States you haven’t heard of.”

Detecting Sinkholes

Depending upon the type of sinkhole, there may be indications that a sinkhole is developing beneath the ground surface. For areas where structures are present, visible signs may include

- Cracks in interior join areas, windows, or doors

- Cracks in exterior block or stucco

- Difficulty in opening doors or windows

- Popping sounds

- Depressions in yards or streets

- Tension cracks in soil or asphalt concrete

- Deep cracks and separations in concrete walks or driveways

- Circular patches of wilting plants

- Leaning trees or fence posts

- Sediment in water

- Sinkhole activity in nearby areas.

Where construction is planned in areas prone to sinkholes or where a sinkhole is suspected, a geologic investigation is recommended. Investigative techniques include exploratory borings, ground penetrating radar, and en electromagnetic conductivity survey. If a sinkhole is found, there are a variety of mitigation measures that can be used to fortify the existing hole and stabilize an overlying structure. Methods commonly used include grouting by pumping or injection; reinforcement with layers of sand, rock, and geotextile fabrics; and underpinning the structure.

Rising Costs and a Growing Problem

The cost to repair a sinkhole can be formidable and is not always covered by conventional homeowner’s insurance. Many insurance companies cover sinkhole-related losses only if “catastrophic ground cover collapse” renders the structure uninhabitable. For lesser claims, special sinkhole coverage must be purchased, often at a high premium. The Florida Senate Committee on Banking and Insurance reported that insurers had received 24,671 claims in Florida between 2006 and 2010, an average of nearly 17 claims a day. The total value of these claims was $1.4 billion. This figure does not include costs for repair of roads, utilities, and other infrastructure affected by sinkholes.

As increasing population drives construction into undeveloped areas and places pressures on existing communities, it is safe to say that the clash between man and sinkholes will inevitably continue. Being aware of the risk of sinkhole formation before, during, and after project development is the best chance of avoiding loss and staying on solid ground.

Note: This article was originally published in an Earth Systems newsletter in the Winter of 2014.