Why Selfies Sometimes Look Weird to Their Subjects

It's not your face; it's how your brain works.

Welcome to the department of discarded selfies, a dark place deep inside my phone where dimly lit close-up shots of my face are left to fade away into the cloud. I’ve thought about sending these photos to friends many times—that’s why I took them, after all—but each time my finger lingers over the share button, a few questions stop me: Why does my face look so weird? Are my eyelids that droopy? Is my chin that lop-sided? And how come nobody warned me?

Taking purposefully ugly selfies encourages photographers to seize control of their self-image by rejecting beauty standards and embracing the imperfect humanity of our faces. But what about earnest selfies that are just accidentally ugly?

Don’t blame your face. Blame your brain instead. Selfies sometimes look strange to their subjects because of how we see ourselves in the mirror, how we perceive our own attractiveness, and the technical details of how we take them on camera phones.

Whether or not a selfie is reversed after being shot is a major factor. If you’ve used multiple mobile apps to take pictures of yourself, you’ve probably noticed that some, like Snapchat, record your likeness as it would appear in a mirror; others, like group-messaging app GroupMe, flip the image horizontally and save your selfie the way others would see you—and this version can be jarring to look at.

Part of that is because our faces are asymmetrical. The left and right side of your face may not seem that different, but as photographer Julian Wolkenstein illustrates with his portraits, which duplicate each side of a face to create strikingly different versions of the same person, that’s not the case. When what we see in the mirror is flipped, it looks alarming because we’re seeing rearranged halves of what are two very different faces. Your features don’t line up, curve, or tilt the way you’re used to viewing them. (An episode of the Radiolab podcast, about symmetry, demonstrated this when it flipped a popular photo of Abraham Lincoln. The asymmetry can be surprising even when looking at images of faces we’re very familiar with, not just our own.)

“We see ourselves in the mirror all the time—you brush your teeth, you shave, you put on makeup,” says Pamela Rutledge, director of the Media Psychology Center. “Looking at yourself in the mirror becomes a firm impression. You have that familiarity. Familiarity breeds liking. You’ve established a preference for that look of your face.”

That’s not just an anecdotal observation, that’s science. According to the mere-exposure hypothesis, people prefer what they see and encounter most often. In terms of self-perception, this means that people prefer their mirror images to their true images, which are what other people see. Experiments conducted at the University of Wisconsin, Madison in 1977 support this idea: When presented with photos of their true image and their mirror image, participants preferred their mirror image while friends and romantic partners preferred their true image. When asked to explain their preference, participants pointed out camera angles, lighting, head tilt, and other differences that didn’t actually exist because the photos were made from the same negative. (According to the founders of True Mirror, which reflects back one’s true image by angling standard mirrors at right angles, only 10 percent of people prefer their real image to their mirror image.)

“The interesting thing is that people don’t really know what they look like,” says Nicholas Epley, a professor of behavioral science at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and the author of Mindwise: How We Understand What Others Think, Believe, Feel, and Want. “The image you have of yourself in your mind is not quite the same as what actually exists.”

The image in our minds, according to Epley’s research, is way prettier. In a study published in a 2008 issue of the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, researchers made participants’ faces more or less attractive in 10 percent increments by morphing their features to resemble composites of conventionally beautiful people (or, for the unattractive versions, people with craniofacial syndrome). When asked to identify their face out of a line-up, participants selected the attractive versions of their faces more quickly, and they were most likely to identify the faces made 20 percent more attractive as their own. When asked to pick the experimenters’ faces out of the lineup, the participants showed no preference for more attractive versions of relative strangers.

“They’re not wildly off—you don’t think you look like Brad Pitt,” Epley says. “You’re an expert at your own face, but that doesn’t mean you’re perfect at recognizing it.”

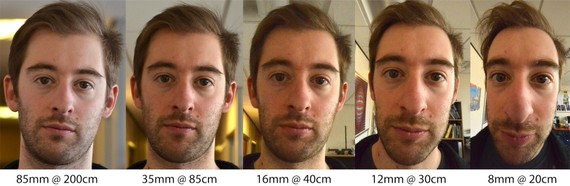

The close proximity of our faces to our smartphone lenses doesn’t make that any easier. Often incorrectly attributed to lens distortion, the way selfies exaggerate certain features is more a matter of geometry, as Daniel Baker, a lecturer in psychology at the University of York, explains on his blog. The parts of your face that are closer to the camera seem larger than other features in comparison to non-selfie photographs, where the distance from the camera to your face is longer and has more of a flattening effect on your face. (Different lenses, such as wide-angle lenses, can alter this effect, but Baker says the differences are negligible.)

So now that you know what makes your selfies “ugly” (to you, anyway), how do you make them more attractive? The Internet is full of suggestions: find good lighting, pop against your background, adjust your angles, and try not to make duckface. But when it comes to making sure your face doesn’t look weird, the answer is simple: Take more selfies, Rutledge says.

“People who take a lot of selfies end up feeling a lot more comfortable in their own skin because they have a continuum of images of themselves, and they’re more in control of the image,” she says. “Flipped or not flipped, the ability to see themselves in all these different ways will just make them generally more comfortable.”