The following is an extract from Rob Smyth’s article from the forthcoming Issue Eighteen of the Blizzard. The Blizzard is a quarterly football journal available from www.theblizzard.co.uk on a pay-what-you-like basis in print and digital formats.

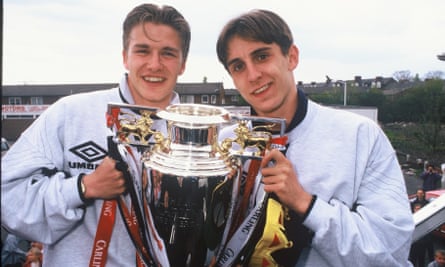

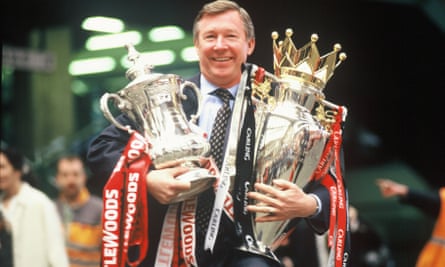

There are two sides to every glory. For every winner there must be at least one loser and the contrast between the two has rarely been as neat as with Manchester United’s Class of 92 and Liverpool’s Spice Boys. They were so different as to make chalk and cheese seem like the perfect sandwich filling. One is a brand, the other a cautionary tale. One maximised their talent; the other pissed their talent up the wall and wore white suits at Wembley. One chose success, the other excess. One claimed a load of leagues and cups, the other collected female trophies. If you count Premier League medals won by the two sets of players, the final score was Manchester United 50-0 Liverpool.

That is how the story is told and, while it does contain an essential truth about the fundamental differences between the sides, it is also a little simplistic. The undeniable greatness of the Class of 92 needs little further exploration, but the story of that Liverpool side is more complex than the received wisdom would suggest. There are multiple interpretations of that era, one of which is that most of the players and the manager Roy Evans should be allowed to embrace and celebrate some of the happiest memories of their life without them being compromised by the phrase ‘Spice Boys’. Robbie Fowler certainly thinks so. In his autobiography he said, “What were incredible times at Anfield – successful, exciting, breathless seasons when I played probably the best football of my career – are dismissed with contempt by those two tiny words.”

This is not to suggest they were blameless. Pretty much all the players acknowledge that, as Fowler puts it, “things happened and they shouldn’t have.” At times they behaved like prats, at times they behaved like another pr- word. There were occasions when it seemed the club anthem had changed to “You’ll Never Drink Alone”. “Win, draw or lose, first to the bar for booze,” was the dressing-room mantra, according to Neil Ruddock. But in the mid-1990s, when the confused celebration of Cool Britannia was at its peak and hedonism was briefly a national pastime, such behaviour scarcely put them in a minority. Nostalgia accentuates the positive in almost everything, yet the Spice Boys are still the subject of ridicule and disdain, seen as laddish underachievers who shamed a proud institution.

The team lost too many important games and in four full seasons under Evans won only the 1994-95 League Cup. The question is whether they won almost nothing because of their reprehensible behaviour or whether their behaviour became reprehensible because they won almost nothing.

They were certainly good enough to outplay the best teams in England. They were the better side in their first five Premier League visits to Old Trafford, yet won none of them. One of those was the 2-2 draw at Old Trafford in October 1995; the Guardian’s Scott Murray said the match “explained 1990s football in a nutshell”, such was Liverpool’s inability to earn a result that was commensurate with their performance. It is a surprise that, for two teams with the perfect combination of attacking ability and mutual distaste, there was no great match between the Class of 92 and the Spice Boys. The 1996 FA Cup final was a notorious stinker. The 2-2 draw earlier that season, a multi-layered minor classic, was the best they produced.

It was a moment in time when Britpop was in full swing and the two groups of players represented the fresh new face of English football after the season of sleaze that was 1994-95. Both teams had nine British or Irish players under the age of 25 in their 14-man match-day squads; their lives and careers would splinter in all different directions but at the time they were peers with similar hopes and fears. If anything, Liverpool’s crop of youngsters were more highly regarded.

All 18 of them were billed as the supporting cast to Eric Cantona, who was returning after his eight-month ban for trying to kick xenophobia out of football. The match turned into a battle of the higher powers: Cantona, Le Dieu, against Fowler, who at the age of 20 was already nicknamed God by Liverpool fans. He didn’t quite steal the show from Cantona – not even the second coming of Jesus Christ could have done that – but he had a damned good go, scoring two exhilarating goals. It was, he later said, “the game of me life”.

Fowler was among many who sympathised with Cantona’s actions at Selhurst Park. “When Cantona went into the crowd to sort that fella out who was giving it to him, I reckon most of the professionals were thinking, ‘Good on you Eric,’” he said in his autobiography. Andy Townsend was even more strident at the time. “I don’t feel an ounce of pity for that bastard supporter,” he said. “I bet his arsehole dropped on the floor when Eric came over.” Cantona was even supported by some of Britpop’s finest, including 3D of Massive Attack, Martin Carr of the Boo Radleys, and Jarvis Cocker of Pulp. “I thought fair play to Cantona. I wish he’d knocked his head off,” said Cocker. “He should have killed him.”

Some of the reaction was as if he had killed him. Cantona felt he was being hounded out of English football and, for a long time, it seemed he would move to Internazionale and play in the hole into which Dennis Bergkamp had disappeared. “I QUIT” was a “MIRROR SPORT WORLD EXCLUSIVE” on 12 April 1995. “Cantona says YES to £3m Inter fortune,” reported Harry Harris.

That did not come to pass and United seemed to be getting over their summer of discontent – on more of which later – when, at the start of August, the FA held an inquiry into whether Cantona had contravened the terms of his ban by playing in a behind-closed-doors friendly against Rochdale. It seemed his ban was going to be extended. Cantona asked for a transfer and went back to France; this time Ferguson was resigned to his departure.

Some of the most important moments in United’s history were influenced by Cathy Ferguson, including her husband’s decision to cancel his planned retirement in 2002, and this was another. “It’s not like you to give up so easily,” she said, “particularly against the establishment.” Ferguson went to Paris in an attempt to talk Cantona round. He avoided the press – whom he had unwittingly tipped off himself “amid the enjoyment of good food and wine” at a book launch the night before – by sneaking out the hotel kitchen and whizzing around Paris on a Harley-Davidson with Cantona’s adviser. A 53-year-old man, on a motorbike in a foreign country, having a midlife crisis of the professional variety.

He met Cantona at a restaurant, which the owner had shut for the evening for this purpose, and got to work, presumably amid the enjoyment of good food and wine. Ferguson homed in on the romantic nerd in Cantona, chatting about the greats of football history to butter him up before turning to matters at hand and persuading him to stay. The FA later backed down over the Rochdale game. “Those hours spent in Eric’s company in that largely deserted restaurant,” said Ferguson in Managing My Life, “added up to one of the more worthwhile acts I have performed in this stupid job of mine.”

Cantona’s ban ended on Saturday, 30 September, which offered Sky the chance to put that weekend’s game back to Sunday, 1 October or Monday, 2 October. It might conceivably have been at home to Coventry or away to Bolton, but even the fixture computer had a sense of theatre: Liverpool (H). These were more innocent times and not everybody twigged that there was approximately a 100% chance that Sky would want to televise the match. When the fixtures were published in the newspapers on 21 June, the Daily Mirror and others led with the fact that Cantona’s first game back would be against Manchester City on 14 October, United’s first scheduled game of that month. Within a week of the fixtures being announced Sky confirmed the match had been moved.

The potential departure and eventual return of Cantona was only one element of the most tumultuous summer of Sir Alex Ferguson’s career. He broke up his first great United side, selling Paul Ince, Mark Hughes and Andrei Kanchelskis. To lose three players might not seem much nowadays; in 1995, when squad rotation was a nascent concept, it was literally more than a quarter of his side. Ferguson had reluctantly decided to modify a team he loved to meet the demands of Europe; he wanted a striker who was sharper around the penalty box, Andy Cole, and felt that Ince had become a tactical liability. That manifested itself in ferocious dressing-room bollockings in 1994-95 during defeats at Barcelona (0-4) and Liverpool (0-2), who were the most European of English sides, a tactical puzzle over which Ferguson pored endlessly. In a strange way, and it’s probably not worth proffering this theory at last orders in Toxteth, Liverpool helped United win the Champions League because of the tactical practice they gave them.

The Barcelona game was the beginning of the end of Ferguson’s relationship with Ince. “You fucking bottler, Incey! You can’t handle the stage, can you?” was Ferguson’s half-time observation. When Ince replied, “Don’t you dare call me a bottler, don’t you dare,” Ferguson walked purposefully over to Ince and hissed in his face, “You are a fucking bottler!” The pair had to be separated by Steve Bruce and Brian Kidd. The Liverpool game, four months later, confirmed Ferguson’s judgement that Ince was getting ideas above his station. Ince struggled to stick to instructions to stay on the left of midfield to neutralise Steve McManaman. When he went on a run of his own down the United right, the ball was headed clear to McManaman, who ran into the space left by Ince to start the move that led to Jamie Redknapp’s first goal. “I sensed that he no longer wanted to be the anchor-man in midfield, where there was none better at the job,” Ferguson wrote later. “It was clear to me that he now saw himself as an attacking midfield player, which was a hopeless misreading of his strengths.”

When Ferguson told the team, at half-time in that match at Anfield, “some of you will not be here if we don’t win the league this season,” it was pretty clear to whom he was talking to. Three years later, when he addressed the team ahead of a vital game against Liverpool in April 1998, it was still bugging him. “We lost the league at Anfield by not listening to instructions about McManaman,” he said in ITV’s The Alex Ferguson Story. Moments later talk turned to Ince, who by then was playing for Liverpool. It was then that Ferguson famously referred to Ince’s “fucking big-time Charlie bit”.

Ince was not the only surprise departure in 1995. Hughes went to Chelsea because he had no wish to be a squad player, while Kanchelskis joined the FA Cup-winners Everton after falling out with Ferguson. The story is told that his agent threatened to have Martin Edwards killed if a deal did not go through. Ferguson said it was “real Godfather stuff”. Later in his career, Ferguson became the master of engineering a fallout to hasten the departure of a player he had decided was past his best. Kanchelskis was one of the few players to do the same to him.

Ferguson did not replace any of them. It was the only summer at Old Trafford when he signed no senior players, though Darren Anderton did turn down a move to United. Ferguson was heavily criticised and in a Manchester Evening News poll 53% of respondents said they thought he should resign. Even allowing for the unreliable nature of polls, this was startling stuff given that, in the previous two-and-a-half years, United had won their first title for 26 years and their first ever Double. As preposterous as it seems now, Ferguson certainly did not have unequivocal support at the club; when he asked to discuss a new contract because he was hacked off that he was earning less than half what George Graham had been on at Arsenal, he did not quite get the response he expected. “Do you think you have taken your eye off the ball?” said Professor Sir Roland Smith, the chairman of Manchester United PLC. “Some people at Old Trafford think you are not as focused as you have been.” Ferguson later said that he felt his job was under significantly more threat in the summer of 1995 than during his enormous struggles in his first four years at Old Trafford. “It seemed that, compared to me, Gary Cooper in High Noon was well off for backers.”

That backstory highlights the extent of the courage Ferguson showed when he decided to rebuild the first team around a load of kids. Ferguson could easily have played safe and brought in a couple of experienced players or kept Ince, but his instinct told him an abnormal crop of young players could wait no longer. Few outside Old Trafford realised the purity of the gold United had discovered. “There are five or six who will certainly go to the highest level, an exceptionally high ratio from any youth team,” said Ferguson. “As always, we try to look for flaws and reasons why we can be wrong but, frankly, we don’t see any.” That was not Ferguson talking in the summer of 1995 but the summer of 1992, soon after they beat Crystal Palace to win the FA Youth Cup. Given the number of variables involved in youth development, it was a heck of a statement. He also said of Scholes that “if he doesn’t make it, we might as well all pack in and go home”.

In January 1993, United demonstrated their faith by giving eight of them four-year contracts. All eight – Paul Scholes, Nicky Butt, David Beckham, Gary Neville, Chris Casper, Ben Thornley, Keith Gillespie and John O’Kane – were not just of the same generation but the same school year. It was like having eight Mensa candidates in the same class.

Ryan Giggs is part of the Class of 92 yet really he was a one-man Class of 91, a regular in the first team from the autumn of 1991. He was only a year older than Scholes, Beckham and the rest but had a head start on all of them. Between them, Giggs and those other eight made 3521 appearances for United.

Some drifted away, with the left-winger Ben Thornley particularly unfortunate; as a young player he was rated higher than Beckham, but his burgeoning career never quite recovered from a serious injury sustained after an awful tackle from Blackburn’s Nicky Marker in a reserve match in 1994. Gillespie might also wonder how different his life would be had Uefa’s foreigner rule been abandoned a year earlier; had it not existed in 1995, Ferguson would not have sold Gillespie to Newcastle as part of the Cole deal.

Ferguson’s overhaul in 1995 was not quite the spectacular clearout that is sometimes painted – Gary Neville and Butt were partially immersed in the side, having started more than 20 games in 1994-95 – but it was still a significant leap of faith and a symbolic transition. And then United were stuffed 3-1 at Aston Villa on the opening day of the season. They were 3-0 down at half-time and, while there were mitigating circumstances in Villa’s excellence (that season they finished fourth, won the League Cup and reached the FA Cup semis) and the absence of Cantona, Cole, Giggs and Bruce through injury or suspension, few cared. The first day of a new season was open season on United and Ferguson. The most famous criticism came that night from Alan Hansen on Match of the Day. “I think they’ve got problems,” he said. “I wouldn’t say they’ve got major problems. Obviously three players have departed. The trick is always buy when you’re strong, so he needs to buy players. You can’t win anything with kids … Aston Villa would have got a massive lift when they saw the team-sheet and it’ll happen every time he plays the kids. He’s got to buy players, simple as that.”

Hansen remembered a lesson from early in his Liverpool career. Bob Paisley told him that, although he had been playing well, he was going to drop him because Liverpool found that, in rare times of trouble, it always paid to go with experience. In truth Hansen’s comments were essentially reasonable; even Ferguson said as much later on. United’s kids were the twice-in-a-lifetime exception that proved the rule, and even then they only won things in 1995-96 because two mature giants, Cantona and Peter Schmeichel, played the best football of their careers during the run-in. Hansen has been nailed for it ever since. He paid for the quality of his soundbite rather than the nature of his criticism. As is the way with these things, all the other criticism of the time – identical in nature, but not as memorable – has been forgotten, as if Hansen was a lone lunatic calling out Fergie and this great crop of kids. He was anything but.

At training the morning after the Villa game, Brian McClair mischievously announced that the team only needed 40 points to avoid relegation. They got 15 of them in the next five league games. A 2-1 win at the defending champions Blackburn, live on Sky on a Monday night, crackled with style and adventure. When Beckham scored a brilliant winning goal, flipping a shot over Tim Flowers on the turn, Ferguson charged from the bench in his suit, his eyes wide and ablaze with paternal pride and excitement. It was like he had just seen a video of the future.

Blackburn began their title defence abysmally, losing five of their first eight games, and it was soon clear that United’s main title rivals were Kevin Keegan’s Newcastle, who started the season spectacularly after the additions of Les Ferdinand and David Ginola, and Evans’s assured Liverpool. Although they lost their early away games at Leeds – in which Tony Yeboah walloped a famous volley – and Wimbledon, they looked the part. A few years before David Brent coined the phrase, Liverpool were a team of chilled-out entertainers. Indeed their young side, built around Redknapp, McManaman and Fowler, were perceived by most, including the England manager Terry Venables, to be more promising than United’s youngsters, partly because they already had plenty of first-team experience. There was a sense that Evans was putting them back on their perch, that the Graeme Souness years had been just an aberration.

“Liverpool are looking ominously threatening again, with a young team which appears capable of greatness if Roy Evans can keep it together,” wrote Paul Wilson in the Observer on the day of their trip to Old Trafford. “United are clearly in transition, experimenting with young players who may take a couple of seasons to mature.” Wilson, referencing Hansen’s comments, then said: “But it may be possible to win the championship with kids like Fowler, McManaman and Redknapp.” Finally he concluded that: “Perhaps you can’t win the championship with kids, but if you throw Cantona into the equation you always have a chance.”

One of Cantona’s most important influences was to teach those young players the value of professionalism and practice, and although it was not especially apparent at the time, there was already the occasional hint of the contrast between the sides. Liverpool were still 17 months away from being called the Spice Boys for the first time but, when they went to Old Trafford, they had just released a charity single and the Sky commentator Martin Tyler noted “there is something of the pop-star image around the club at the moment.”

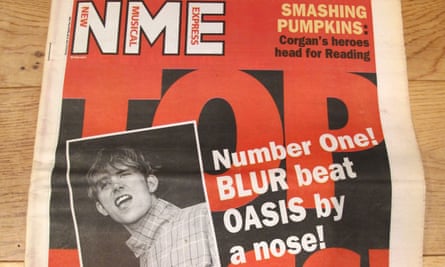

Britpop was close to its peak when the sides met on 1 October 1995. (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? by Oasis was released the following day; Blur’s The Great Escape had come out on 11 September. Just after United and Liverpool finished playing, Pulp’s Sorted For E’s & Wizz – which prompted a “BAN THIS SICK STUNT” headline on the front page of the Daily Mirror, because the sleeve included instructions on how to fold a speed wrap – entered the singles chart at No2. Some of it looks naff with hindsight, nostalgia’s cynical sibling, but it remains the most exciting time to be a young person since the 1960s. Millions of middle-aged people will always recall this as the time of their lives.

It would be overstating it to paint United v Liverpool as a football equivalent of Blur v Oasis; Newcastle were the best team in the country at the time, and the only person on either side who led the Nine O’Clock News – as Blur and Oasis did when they released their singles Country House and Roll With It on the same day – was Cantona. Yet the youthful vigour of both sides reflected the mood of the times and there was considerable excitement as to what these players might do against each other – and together, for England – in years to come, even if the phrase “golden generation” was not really part of the football lexicon back then.

The previous season had been full of controversy, with Cantona’s suspension, match-fixing allegations against Hans Segers and Bruce Grobbelaar, George Graham being sacked for allegedly taking a bung, Paul Merson going into rehab, a riot at the friendly between Ireland and England, and plenty else besides. On the cover of their end-of-season review, FourFourTwo said it was “THE YEAR FOOTBALL WENT MAD!” With so many young players, and exciting new foreign signings like Bergkamp, Ruud Gullit, Ginola and Georgi Kinkladze, it felt like a new beginning; a time of innocence and hope in which there was a pervasive sense that anything was possible.

Dyed blond hair was briefly in vogue around the time. Paul Gascoigne did it at Euro 96. Robbie Williams – in his “fat dancer” phase between Take That and solo success, to use Noel Gallagher’s phrase – did it. So did Fowler, who went on a summer holiday to Faliraki in which he and all his mates, including the young Liverpool defender Dominic Matteo, bleached their hair. “It obviously made me look fucking stupid,” he said in his autobiography. Beckham did a million different things with his hair once he became a celebrity. But you suspect that had Beckham or any of the other United youngsters dyed their hair blond at that stage of their career, Ferguson would quickly have dried it.

In September 1995, Ferguson was irritated by something else instead: the hype over Cantona’s comeback. It was the subject of a daily countdown in many newspapers; the coverage looks light compared to the post-Sky Sports News nightmare of 2015, but at the time it was unprecedented and wearying for those involved with the two teams. Ferguson was tired of talking about Cantona; Evans was annoyed that his team were seen as extras.

There were some recurring themes in the previews, primarily the fear that hairy-arsed Neanderthal defenders would provoke Cantona until he cracked again. One hairy-arsed Neanderthal defender in particular. Ruddock had clashed with Cantona in Liverpool’s previous visit to Old Trafford, a 2-0 defeat in September 1994 in which they were much the better team for an hour. Ruddock repeatedly turned down Cantona’s collar to win a bet he had with a local comedian called Willie Miller. Cantona responded with the kind of nasty challenge which would been a straight red now but which in those days usually ended with the commentator observing that the offender was fortunate not to have his name taken. Cantona then made a promise to Ruddock: “Me and you, we fight in the tunnel.”

When the game ended Ruddock asked David James, the biggest bloke in the Liverpool team, to walk off with him. Afterwards he was on the booze in the players’ bar – Liverpool had lost, after all – when Cantona tapped him on the shoulder. As he turned round, Ruddock was sure it was about to kick off; Cantona winked, handed him a pint and walked off. That, at least, is how Ruddock recalls it.

Before their next Old Trafford meeting, Bruce made a plea for fellow professionals not to act the goat, as did the PFA’s Gordon Taylor. Intriguingly, that’s exactly what happened. Cantona was subject to scarcely any provocation throughout the season, which makes little sense. Two possible reasons stand out: respect and empathy for how Cantona reacted at Selhurst Park, and a swift realisation that a new, calmer Cantona had returned and that provocation would be a waste of time.

It was widely noted that Cantona had not really apologised for his actions, and there was a bit of faux outrage at the tone of the Nike publicity celebrating his comeback. “He’s been punished for his mistakes, now it’s somebody else’s turn,” read a banner with Cantona’s face. There was also a television advert in which Cantona did say sorry, sort of. “Hello,” said Cantona, looking straight to camera. “I want to make an apology. I have made some terrible mistakes. Last year, in a certain 5-0 victory [against Manchester City], I only score one goal. Against Newcastle I put the shot three inches wide of the post. And at Wembley I fail to complete an ‘at-trick. I realise this behaviour was unacceptable and I promise not to make such mistakes again. Thank you.”

Over 100 press men turned up for a practice match at Old Trafford on the Thursday, with Cantona scoring the winning goal past Schmeichel in a 6-5 victory. “Lock up your daughters and jump aboard the trawler; the sardines and seagulls will surely follow,” said the Times preview of the game. On the first day of October, autumn sunshine came to Manchester for Cantona’s return.

In the Guardian, David Lacey called it “A Mancunian version of Bastille Day”, such was the preponderance of berets and French colours on flags and faces. The DJ played the Plastic Bertrand punk hit “Ça plane pour moi” before the game, while plenty was made of the fact one of the linesmen was called Messiah.

There were no Liverpool fans at the ground, officially at least, because of capacity restrictions. The attendance was 34,934, the last time a crowd of less than 40,000 has watched a United v Liverpool game. The teams started the match in third and fifth respectively, behind Newcastle – who had won seven of their first eight games – and Aston Villa. Leeds, in fourth, were between the sides.

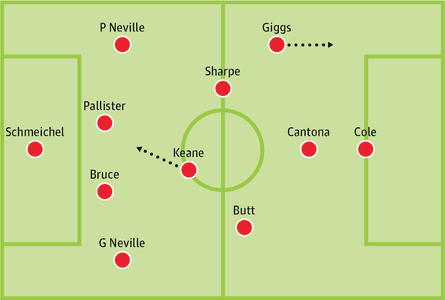

After being absent for 32 matches and 248 days, Cantona took 67 seconds to create the opening goal for Nicky Butt. “Who could have written such a script?” said Ferguson. It was an instant reminder of one of Cantona’s greatest skills: the ability to find space away from the headless chickens of 1990s English football, often by just standing still. He was a singular man who frequently stood alone on the pitch. In this case he was on the left wing, drifting into the space when Liverpool’s right wing-back Jason McAteer pushed forward.

Roy Keane, United’s midfield guvnor in nature if not name after the departure of Ince, harassed McManaman into conceding possession just inside his own half. A snappy pass from Butt and a smart off-the-ball run from Keane gave Cole the chance to release Cantona on the left wing. He took his time, lifted his head – his collar was not the only thing he wore up on the field – and then, as a series of players ran towards the goal, lazily drifted the ball back the other way to the late-arriving Butt on the edge of the area.

Butt’s unusual first touch, which was either brilliant or fortuitous, or possibly both, was effectively a through ball to himself. It looped the ball over Phil Babb and into the space in front of David James. As James rushed out, Butt looped the ball over him as well and it went into the net as Ruddock on the line leapt after it like an arthritic acrobat.

It was that rarest thing, the goal in which the goalscorer is not the main man. “Cantona has made a goal for Nicky Butt!” said Tyler on Sky. While most of the players left Butt at the bottom of an impromptu bundle on one side of the field, Giggs and Gary Pallister ran straight to congratulate Cantona on the other.

As is so often the case, an early goal meant that the scorers conceded the territorial advantage and Liverpool started to settle into their hypnotic passing routine. After six minutes Redknapp, given too much room, cut across a fine 25-yard shot that swerved just wide of Schmeichel’s left-hand post. As Andy Gray observed on Sky, the desperate nature of Schmeichel’s dive betrayed how uncomfortable he was. Near misses at Old Trafford were becoming frustratingly familiar for Redknapp; on the previous visit 13 months earlier he twanged the crossbar from 20 yards. There would be another before the game was out.

Redknapp, aged 22, was emerging as a significant talent for both Liverpool and England. He made his international debut a month earlier against Colombia – it was his mis-hit cross that led to Rene Higuita’s scorpion kick – and started the next two matches as well. He was comfortably ahead of United’s two young English midfielders, Butt and Beckham, in Venables’s plans. (Scholes was a No10 in those days.) With Ince absent from the side at that time as punishment for pulling out of the Umbro Cup in the summer of 1995, Venables was leaning towards a ball-playing central-midfield partnership of Redknapp and Gascoigne at Euro 96. Then Redknapp came off injured after seven minutes against Switzerland in November 1995 and was out for three months. Ince, after finding a way back in, showcased his superior defensive ability and started at Euro 96, where he performed with his usual under-appreciated brilliance.

Even then, Redknapp could have played a huge part in the tournament. He turned the game when he came on at half-time in the 2-0 win over Scotland, instantly greasing England’s passing wheel and starting the move that led to Alan Shearer’s opening goal. When he came off injured with a few minutes remaining, Venables told him he would start the next group game against Holland. But the injury was far more serious than anybody had realised and he missed the rest of the tournament. Given that the fading David Platt started against both Spain and Germany because of suspensions to Ince and Gary Neville, it’s probably fair to assume Redknapp would have played both games. With his form and confidence so high, they might have changed his life. At 22 you assume the moment will come again; it frequently does not. Redknapp never did start a game for England at a major tournament. That was his moment. Venables, who rated him so highly, was scheduled to quit after Euro 96 and his replacement, Glenn Hoddle, preferred the double security of Ince and David Batty. By March 1998 Redknapp was playing as a sweeper for the Under-21s as an experiment.

This is not to say Redknapp would definitely have made it; we simply don’t know. But with a fairer wind and a different course of events, he might have become a top, top player. Those two injuries against Switzerland and Scotland did so much damage. “The way I look at it, at least I didn’t come off because I was crap,” he said later. “I was playing really well at the time, but that’s life.”

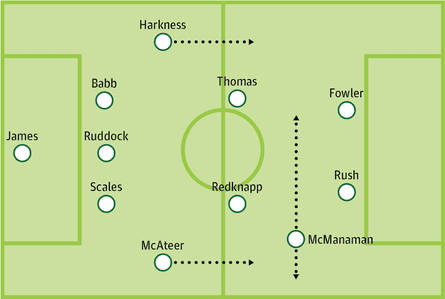

Redknapp was a key part of a five-man Liverpool midfield, the main reason why they stretched Ferguson much more tactically than any other English side in that period. Their formation was not unusual – more than a third of Premier League sides played with three at the back that weekend – but the quality with which they moved the ball in the middle of the pitch set them apart. Long before Ferguson coined the phrase to describe Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona, Liverpool’s passing carousel drove him to distraction, and to his chalkboard. The three in the middle were usually Redknapp, John Barnes – whom Evans moved infield to be his “eyes and ears” on the pitch – and McManaman wandering behind the front two.

Sometimes their domination could be a little sterile but they had an easy, sophisticated style and were by some distance the most continental English side. When Evans was appointed, the Liverpool chairman David Moores called him “the last of the Boot Room boys” because of his emphasis on passing and movement. Liverpool’s FA Cup final record that year was even called “Pass and Move (It’s the Liverpool Groove).”

Ferguson was fixated with stopping McManaman dictating the play; it became Groundhog Team Talk. “We’ve heard it every time we’re playing Liverpool – McManaman’s doing this … We know that,” said Schmeichel in The Alex Ferguson Story in 1998. “He doesn’t really have to tell us, because we know. I think he likes team talks …”

Ferguson become tactically obsessed in his later years, but for most of the 1990s, domestically at least, he sent his team out in a 4-4-1-1 formation almost without thinking. Liverpool were different. Their extra man in midfield, and McManaman’s influence, led Ferguson to try all kinds of things against them. His plans included Denis Irwin in midfield against McManaman, with Jordi Cruyff as a left wing-back; Ince on the left of midfield; a 4-1-3-2 in the 1996 FA Cup final; Cantona up front on his own; and a team without wingers. On this occasion he started with an unbalanced 4-4-2 formation with no right winger. Butt was nominally on the right side, but in reality he was tucked in to provide support for Keane and Lee Sharpe, with Giggs out on the left wing.

At the start Butt’s main role was offensive; after giving United the lead, he made two dangerous breaks in the inside-right channel onto passes from Cole and then Cantona, the latter a beautifully cushioned first-time volley. Each time Butt was at a very narrow angle to the right of the box and each time James came out to smother the chance.

Even at that early stage, however, United were playing largely on the counter-attack. Despite having no fans and going behind, Liverpool settled calmly and quickly into an authoritative passing game. McManaman started to the right of centre, but he or somebody on the Liverpool coaching staff soon sussed that, with Butt tucked in, Liverpool could outnumber United on the other side. McManaman moved over to spend most of the first half in an inside-left position, from where he routinely fed either Fowler or the overlapping wing-back Steve Harkness. He was so desperate for the ball that at one stage, with Liverpool probing to their right, McManaman stood on the other side of the pitch with his hand up like an enthusiastic pupil.

Liverpool’s dominance was such that United barely got out of their half for a 10-minute period towards the end of the first quarter. There was an increasing nervousness around the ground, with the crowd roaring with a mixture of fear and defiance. Although United had recovered from that dismal opening-day defeat at Villa, there was still no real certainty about how good the team was or would be. All the old security of watching the Double side of 1994 had gone. In their previous two home games, United had lost 3-0 at home to York in the League Cup and gone out of the Uefa Cup on away goals after a 2-2 draw at home to Rotor Volgograd. Old Trafford wasn’t exactly a fortress.

Liverpool created their first clear chance in the 23rd minute, Redknapp drove a fine cross-field pass to Fowler on the left wing. As Bruce huffed and puffed toward the danger with misplaced determination, Fowler showed him just enough of the ball to make him think he could win it. Bruce made his move, Fowler slipped the ball between his legs and was away. Then, as Pallister came across, he lazily chipped a gorgeous, curving cross towards Rush at the far post. It bisected Phil Neville and Schmeichel, but the stretching Rush sliced it wide of an open goal from three yards. It probably wasn’t quite as bad a miss as it looked, with Rush possibly unsighted by the scrambling Schmeichel in front of him, though that didn’t stop a hearty “WAHHH” from the United fans for a man who scored only one of his 346 Liverpool goals at Old Trafford. “It’s a beautiful ball in from his strike partner,” growled Andy Gray with the envy that only a former centre-forward could manage.

After a slow start to the game, Fowler had sprung to life. The same was true of his season. He was left out for a few games early on after coming back for pre-season with “dyed blond hair and a lairy attitude … They were right to drop me.” He was also all over the tabloids with blood streaming from his nose when, after one prank too many, Ruddock punched him at an airport in September.

Liverpool had tried all three combinations of Rush, Fowler and Collymore at the start of the season, but it was soon clear that it was going to be Fowler plus one. That was expected to be Collymore, with Rush, at the age of 34, to wind down his career with the footballer’s equivalent of the reduced working week. Collymore was a revelation for Nottingham Forest in 1994-95, wowing Ferguson with his performances against United, and Evans was so keen to sign him that he flew back to London from a family holiday in St Lucia for a one-hour meeting with Collymore before returning to the Caribbean. But after signing for £8.5m, a British-record fee, Collymore made a relatively poor start to his Liverpool career. That was despite a storming long-range goal against Sheffield Wednesday on his debut, and then another against the champions Blackburn in September. “In that moment it felt as if the move to Liverpool was already turning into some wonderful dream that was going to propel me right to the very top and force me into the England team,” he said of the Wednesday goal in his autobiography. “It felt like everything was possible.”

Not just on the field, either. Even before he joined Liverpool, Collymore found a lifestyle that gave new meaning to fantasy football. On the penultimate weekend of the 1994-95 season, he met up in London with a number of Liverpool players, some of whom he had befriended on England duty. In his autobiography he says that, when he went to knock on one player’s door, he got a bit of a surprise. “It was always the custom with footballers in those days that you would leave the door to your room open when you were sleeping,” he said. “Sure enough the door was ajar. I pushed it open and walked in. I stopped dead in my tracks as soon as I saw the scene unfolding in front of me. One of the players was sitting propped up on the bed, hands behind his head, looking like a prince. Further down the bed, two girls were busy sucking him off. Both of them working away at him and him just sitting there watching them go. I stared at it all for a second in disbelief. Welcome to the Premiership, I thought. Then I went back downstairs.”

In his own autobiography, Fowler references the story – there is no suggestion it is necessarily about him – and dismisses it. “Hmmmmm,” he said. “Seems a bit strange that you would be in a large, busy hotel with two girls, and not even bother closing the door.” There are so many stories about the Spice Boys that, as Fowler says, “it is hard to know what it true and what is myth.” This is particularly true of their romantic and sexual exploits. In 1995, FHM published their first list of the world’s 100 sexiest women. By 1996 and 1997, it was easier to tick off those who hadn’t been linked with a Liverpool player. When Phil Babb started dating the Loaded glamour girl Jo Guest, the situation had almost gone beyond satire. “We were the first players to get big money, Porsches and Ferraris and get page three birds into bed,” said Ruddock. “We rewrote football history, really. It was great fun, looking back.”

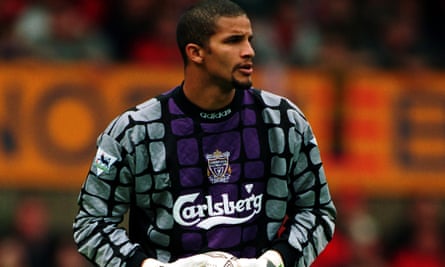

Redknapp had a column in Smash Hits; McAteer did a shampoo advert. James appeared in 50-foot Armani poster in his underpants. There was a probably apocryphal story about James being told by Evans that he would be fined if he went to an Armani show in Milan and paying the fine in advance there and then.

Milan may have been off limits, but London was not. After many home games, a group of players headed straight to Manchester Airport for a night out in London. Mick McCarthy was surprised when, after leaving one Liverpool game early, he then saw all the players at the airport waiting for the same flight. The identity of the players who went to London varies from tale to tale, though most agree it was mainly the southern lads. Fowler says it was Redknapp, Ruddock, Babb, Scales, James and occasionally Thomas, McAteer, Mark Kennedy and Collymore. They were usually in one of their three favourite nightclubs – Chinawhite, Ten Rooms or the Emporium – by 9pm.

“From what we heard, they all had a very good strike record with the women in London,” said Matteo in his autobiography. “The problem was that every single member of the squad was tarred with the same brush, which always used to rile me and Razor. We didn’t want any part of the London scene and instead preferred going to our local boozer in Formby, The Grapes, on a Saturday night.” And a Sunday morning. “A typical night involved sinking 20-25 pints of Guinness, a bottle of port between us and a few shots.” After a lock-in, often till 5am, they would reconvene at 10am on the Sunday for a champagne breakfast and another 12-hour session. The sheer volume of booze is extraordinary, but only to modern eyes. In those days it was the norm. During Arsène Wenger’s first pre-season tour as Arsenal manager in 1997, Steve Bould ordered a 35-pint round for five people. They won the Double that year. A year earlier, in his season diary, Ferguson reflected that Keane “thinks Guinness is medicine”. United won the title that year; Keane was their best player.

Even so, the apparent contrast with their Manchester rivals was clear. United lived for injury time, when they scored those euphoric winners and equalisers; Liverpool lived for the third half, a phrase used in Denmark to describe the post-match piss-up. “I didn’t see life until I was 27!” said Gary Neville of his monastic lifestyle. “It doesn’t work for every player,” he said in Red, his autobiography. “A dressing room full of Gary Nevilles would be boring. But you cannot stay at the top in professional sport for very long without commitment and sacrifice – and there’s no doubt that, as a squad, we had good habits. Times were changing. Gone were the days when footballers could afford to get pissed in the week.”

Sadly Opta does not keep data on average pints drunk per week by Premier League footballers each season. The culture slowly started to change in the mid-1990s, with an increasing foreign influence, though it was a few years before ice baths and Gatorade chasers were the norm rather than the exception. United had some monumental sessions of their own, though they tended to prioritise quality rather than quantity of piss-up. “At United,” said Neville, “the time to party is when you’ve won something.”

It would be interesting to know the extent to which United were exposed to the same temptations as Liverpool. They would surely have found them easier to resist; partly because of their nature and partly because their manager famously had spies all over town who would inform him if any of his young players were seen ordering a ginger ale in the week. The idea that Ferguson stamped out the drinking culture at United straight away is demonstrably untrue; but he certainly went out of his way to patrol his young players’ lifestyle and encourage them to settle down. Not even the Catholic Church espoused the virtues of marriage as much as Ferguson.

Liverpool were young, free and single, mostly, although Scales says the stories of their excess were a little overplayed. “We had great fun, although it wasn’t particularly vulgar or reckless behaviour,” he says in Simon Hughes’s excellent Men in White Suits. “We tried to keep things as normal as possible. We were like any other group of lads. We did some daft things. But there were lots of half-truths. Maybe we did spend money on a car. But it was never as much as people said. Maybe we did go out in Soho. But we never stayed out quite as late as it was made out.”

Even after that first match, when “everything was possible”, Collymore expressed surprise in his post-match interview about how little he had seen of the ball. Liverpool’s intricate style was completely alien to him; for most of his career, teams had used his pace and power where possible. Collymore thought his honesty would be constructive but it soon backfired.

A few games into the season he gave an interview to FourFourTwo, in which he raised the same concerns. “I don’t know any industry that would lay out £8.5m on anything without thinking how they’re going to use it,” he said. “From that moment all the lads were going, ‘Aye aye, who the fuck does he think he is?’” said Fowler. “There was suspicion of him from then on.” The mutual mistrust started to perpetuate itself and Collymore never truly settled at Anfield. His decision not to relocate from Cannock to Merseyside increased the sense that he was an outsider. There are some who will tell you his impact on morale is the biggest single reason for Liverpool winning nothing in his two years at the club. In Red Men, his history of Liverpool, John Williams says: “His signing turned out to be the equivalent of a managerial suicide note.”

Evans disputes that. “No, because for the first 18 months he did what we wanted him to do,” he said. “He came here and he was a player. We paid a big fee but he did the business. But after 18 months he started not to turn up; the press got onto the case – they would look to see if his car was there and it became ‘Stan Collymore watch’ – it became difficult for the lads. You’d fine him, then he wouldn’t play for the reserves. For the good of the team we had to sell him. It was all really because he didn’t move up from Cannock.”

Collymore deserves a lot more credit for the extent to which he adapted his game as his first season at Anfield progressed. He started to come deeper and wider, as Liverpool wanted, a tactic that was most obviously successful when his wonderful cross created Fowler’s opening goal in the legendary 4-3 win over Newcastle in April 1996. Collymore also scored twice that night and ended with 19 for the season. In January 1996, he and Fowler were even named as joint Premier League players of the month.

Towards the end of his second season Collymore’s differences with Liverpool became irreconcilable. Evans wanted to replace him with Teddy Sheringham, but the board would not sanction a deal because he was too old. “I’ve got to be honest,” said Fowler, “I would have killed to have had Teddy providing service for me.”

Barnes says Collymore bore comparison with the Brazilian Ronaldo – pace, two good feet and dribbling ability – but that he was too selfish. Intriguingly, Collymore had been targeted by Ferguson in December 1994, just before he bought Cole. Had Frank Clark not lied about having the flu to stall Ferguson, Collymore might have joined United in January 1995. It’s conceivable that, had that happened, he might have become one of the world’s best forwards. But it’s also conceivable that he might have been a major problem in the United dressing-room, such was the societal ignorance of mental illness at the time. Nobody really knows.

For the first few months of the 1995-96 season, Liverpool were massively dependent on Fowler for goals. He did not disappoint. After hitting four in a 5-2 win over Bolton the previous weekend he had increasing joy against Bruce, who was 34 and in his last season at the club. When McManaman’s pass infield deflected to Fowler in the box, he fell over under considerable pressure from Bruce. With the limited camera angles it’s hard to discern a clear offence – Bruce made it look clumsy and therefore hard categorically to give a penalty – yet all football instinct suggests it was probably a foul. Fowler’s reaction reinforced that; he ran straight after David Elleray, his face a picture of outraged confusion. “It was a definite penalty,” he said after the game. “If I’ve got a clear shot at goal there’s no way I’m gonna dive or go down.” United were in a long run of 2247 days without conceding a penalty in the league at Old Trafford, from December 1993 to January 2000, though there were a few in European games in that time.

Sharpe almost compounded Fowler’s frustration in the 32nd minute when he missed a great chance to put United 2-0 up. After a clever dummy from Giggs, who danced past the ball to allow it to run further across the area, Sharpe sidefooted meekly and too close to James from 10 yards with his right foot.

A goal then would not so much have been against the run of play as an affront to it. His chance was so great that, in a sense, when Fowler scored 28 seconds later it represented a two-goal swing, from 2-0 to 1-1. McManaman eased an angled pass to Fowler, given a bit of room by Bruce by the left corner of the box. He took a touch and scorched a shot that flew past Schmeichel and into the top corner at the near post. Schmeichel was beaten for pace and by the element of surprise, though he didn’t help himself by unconsciously planting his weight on his left foot a fraction before Fowler hit the shot.

Fowler said that beating Schmeichel at his near post “pleased me just about as much as any goal I’ve ever scored.” Schmeichel had an aura that his peers recognised – even if they did not recognise it formally. Bizarrely, he was included in the PFA Team of the Year in only one of his eight seasons at United.

Human nature being what it is, United had close to an even share of possession in the 12 minutes between Fowler’s goal and half-time. Yet there was a manic edge to their attacking: Liverpool looked the calmer, classier side.

Ferguson made a significant tactical change at half-time, switching to a 3-5-2 system to match Liverpool. Beckham, on for the injured Butt, played in the centre alongside Keane and Giggs, with Sharpe moving to left wing-back, Phil Neville to right wing-back and Gary Neville to centre-half. At that stage there were still many who thought he would end up at centre-half. “If he was an inch taller he’d be the best centre-half in Britain,” said Ferguson later that season. “His father is 6ft 2in – I’d check the milkman.”

The change had little immediate impact, although Cantona, boxed in by the corner flag on the right, somehow manufactured a vicious low cross that only just evaded Cole. But Liverpool picked up possession where they left off at half-time and were soon threatening to take the lead. Thomas eased a pass into Fowler, who had his back to goal 30 yards out. With Bruce and Pallister both charging towards him, Fowler stabbed an ingenious spinning pass in behind both of them to allow McManaman to run into the box on the right. He fell over as Keane came across him, prompting another big penalty appeal that was rejected by Elleray. Keane ran away a little sheepishly, though replays suggested McManaman had made the most of a fleeting touch of his chest.

Any sense of injustice lasted only until the 52nd minute, when Liverpool were appeased by a second goal from Fowler that was a majestic fusion of attitude and aptitude. Thomas curved a penetrative pass around Gary Neville towards Fowler, who fairly but aggressively shoved Neville aside and then, as Schmeichel came out, chipped the ball over him with his right foot. The chip was struck so early that it took Schmeichel out of the game before he even realised he was in it and hit the net to what Fowler called “the sound of tumbleweed”. Neville complained to the referee but deep down, you suspect, he knew he had fairly lost a battle of strength. It was a vital lesson about man’s football, albeit from someone six weeks younger than him. Nobody ever did that to Neville again.

The goal summed up the sheer irrepressibility of Fowler at that time. Later in the year he would become only the second person, after Giggs, to retain the PFA Young Player of the Year award. There may have been one or two better players in the country – Alan Shearer was at his very best – but there were none more exhilarating or charismatic, and none who captured the spirit of the times better. Indeed it’s hard to think of any footballer in modern times who has encapsulated the joy of youth quite like Fowler.

In that period he was like a cross between Liam Gallagher and Ferris Bueller, full of swagger and anarchic mischief. He was the Anfield rapscallion, both puckish and punkish, who derived enormous pleasure from goading and embarrassing his elders. It was nothing personal, just a bit of fun, the same as when he and McManaman bought two horses and called them Some Horse and Another Horse to confuse commentators and people listening in the bookies. He gave Bruce an almighty chasing in this game and later in the season scored a stunning goal against Aston Villa, making a fool of Steve Staunton with a flick behind his standing leg before sweet-spotting insouciantly into the far corner from 25 yards. Everything he did looked instinctive, natural and effortless. “He was,” said the writer Mike Gibbons, “a man with not one scintilla of doubt in his ability.”

Fowler scored more than 30 goals in each of the three seasons from 1994-97, but would never again reach 20. Many point to the obviously debilitating effects of a cruciate-ligament knee injury in 1997-98, but other factors also conspired: the emergence of Michael Owen did not help, and he suffered under the regime of Gérard Houllier. Perhaps most significant is that, like Oasis, his success was inextricably linked to the freedom of a youth that was in intrinsically finite supply. He went too far occasionally, but who cares? For the most part Fowler was the most magnificent advert for immaturity. Arguably he reached the top of the mountain when he scored twice in the famous 4-3 win over Newcastle in April 1996; it was five days before his 21st birthday.

He scored two outstanding goals in the League Cup and Uefa Cup in 2001 as part of Liverpool’s treble, but most people only remember the early Fowler. In football terms he lived fast and died young. That only adds to the appeal.

Nobody has ever given vicarious pleasure in quite the same way as Fowler, because nobody has ever captured what it’s like to be young, free and brilliant in quite the same way. The Liverpool fans worshipped him. So did many of the players; Matteo had him on speed-dial as ‘God’. “Without doubt he was the best player I have ever played alongside,” said Collymore, even though the two didn’t particularly get along. “Playing with him – even for someone like me, who fancied himself – was an education.”

Fowler’s second goal at Old Trafford changed the manner of the game as well as the score. A combination of United’s wounded pride and Liverpool’s subconscious retreat meat that United dominated the game for the first time, though never quite to the same extent as Liverpool had for the best part of an hour.

They started to create chances, with Beckham – who in those days told anyone who would listen that he was a central midfielder – impressing with some his passing and, yes, dribbling in the centre of the pitch. An angled pass put Cole through, with James doing well to concede a corner as Cole tried to go round him. Cantona’s dramatic snap-volley was also blocked by Ruddock.

After 71 minutes, there was the second significant part of Eric’s personal journey: an equaliser from the penalty spot. Liverpool kept the ball for almost a minute, during which McManaman produced a double dragback that had Gray purring on Sky. Then Phil Neville impatiently crunched Thomas on the halfway line, sparking a United break. As Cantona moved towards the area, Giggs made a devastating surge past first Redknapp and then Cantona, whose gentle, no-look through ball ushered Giggs through on goal. Redknapp slid in, Giggs fell over and the ball was deflected just wide of the post. Giggs sprung to his feet, looking quizzically into the sun at the referee Elleray. It was not clear what had happened, or what was about to happen, until Sky’s Martin Tyler exclaimed: “Penalty!” It looked questionable at the time – Fowler called it “predictably dodgy” in his autobiography – but with every replay it looked a better decision. Redknapp certainly held Giggs’s shirt and did not appear to get the ball with his tackle.

As they waited for the penalty around Old Trafford, the crowd broke into a chant of “Ooh Aah Cantona”, though it was tinged with a nervousness that there might be a sting in the fairytale. Cantona had never missed a penalty for United, surely he wouldn’t miss one now? Of course he wouldn’t. At that stage penalties were almost as simple as box-ticking for Cantona. Run up slowly, wait for the keeper to move, pass it gently in the other direction. He didn’t send the keeper the wrong way so much as wait for the keeper to send himself the wrong way. Cantona celebrated his cathartic equaliser with a joyous, impromptu pole dance behind the goal.

Those two minutes were the Class of 92/Spice Boys rivalry in miniature: pretty possession football from Liverpool, a decisive thrust from United.

Ferguson, sensing blood, brought on Scholes for Phil Neville and moved Beckham to wing-back. At that stage Scholes generally played as a No10, so the central-midfield role into which he was pushed was a little unusual, and a reflection of United’s sudden aggression after a game in which they had largely been preoccupied with containment. The same had happened a year earlier, when they were outplayed for two-thirds of the match before overwhelming a flagging Liverpool with two late goals.

In a sense, Cantona had scored one and created two of United’s two goals, such was his part in the penalty award. He inevitably tired as the match progressed and never really threatened to complete the story by scoring a winning goal. He almost created it, though. After a slick move, Cantona drifted a chip towards Cole, whose scintillating overhead kick went just wide. Cantona’s frustration with his declining influence manifested itself when he was muscled aside in the box by Ruddock. It wasn’t a foul and Cantona knew that, though he was sufficiently irritated to demonstrate to the referee, using the universal hand signals for corpulence, that Ruddock had multiple chins and a D-shaped stomach.

The match was drifting towards an honourable draw when, with 29 seconds of the 90 minutes remaining, Beckham clumsily fouled McManaman a fraction outside the box. Redknapp’s quick and quick-witted free kick was probably going to hit the outside of the far post; Schmeichel, scrambling desperately across goal, made sure with a fingertip save.

“We got off to a dream start, then we forgot we were playing a game of football,” said Ferguson after the match, suggesting the occasion had got to his team. “The hype’s over, thank goodness.” At his post-match press conference he looked shattered, with his right hand resting on his face, and wearily snapped after one question too many. “You know what I’m gonna do here? I’ve finished talking about Eric Cantona. I’m happy to talk about the game. I’ve done enough talking about Eric Cantona. Youse are unbelievable, you people.”

The media weren’t the only ones talking about Cantona’s comeback. “Wasn’t it good to see Eric Cantona back in action?” said Tony Blair, who saw no reason to let basic facts, such as where Cantona kicked Matthew Simmons, get in the way of a cheap PR line. “Let’s hope this time he remembers kicking people in the teeth is the Tory government’s job.”

After playing in the League Cup second leg at York two days later – United won 3-1 but went out 4-3 on aggregate – Cantona’s rehabilitation continued the following Saturday with a reserve match against Leeds. There were no Premier League games because it was international week, so the crowd at Old Trafford – 21,502 – was the largest in England that day.

After the initial high, Cantona struggled. Two brilliant goals in a 2-2 draw at home to Sheffield Wednesday were his only goals from open play in his first three months back. He would stir gloriously when 1995 turned into 1996; but there was a time when it seemed he had lost his edge. Indeed, if you had said after the match at Old Trafford that one of the two teams would do the Double that season, most would have gone for Liverpool. “For long periods their superior passing and vision dominated the match,” wrote the peerless David Lacey in the Guardian. It was becoming a recurring theme for Liverpool at Old Trafford: in five consecutive league games, from 1992-93 to 1996-97, they were the better side, yet they lost three and drew two.

The stock line on the Spice Boys is that they were not very good at winning ugly; the bigger problem was that they were the best around at losing pretty, or in this case drawing pretty. Not just at Old Trafford, either. In November 1995 they completely outpassed the runaway leaders Newcastle at St James’ Park, and lost 2-1 after a late fumble from James. This kind of thing happened far too often to be coincidence, and confirmed they did not have that indefinable something that would have turned a bloody good team into a great one. In ITV’s Sports Life Stories episode on John Barnes, Steve McManaman identified the problem. “There was always something a little bit … weak” – he twists a dial in his head – “in some of our players in certain games, which cost us.”

In a notorious defeat at home to bottom-placed Coventry in April 1997, which derailed their title challenge, Liverpool played gloriously for an hour and took the lead before losing to two set-pieces, the second bringing another mistake from James. As time went on, so such matches became tinged with an element of farce; Liverpool were a team who could always snatch defeat from the jaws of dignity. They had a Frank Spencer gene.

Like any set of lads with a taste for the booze, they were also prone to lost months. That Newcastle defeat in November 1995 was the start of a desperate four-week period which Liverpool took two points from five games, slipping from third to eighth, and went out of the League Cup. Yet the end of that bad run overlapped with a four-month unbeaten run, at the start of which they slaughtered United, Arsenal, Nottingham Forest and Leeds in consecutive home games. Even Mystic Meg wouldn’t have bothered trying to predict what Liverpool would do next. When they beat Newcastle 4-3 to get back in the 1995-96 title race, they lost 1-0 at relegation-threatened Coventry three days later and were back among the also-rans.

The perception that Liverpool were good-time Charlies who bottled the big games was reinforced by their record against Everton. They failed to win in nine derbies, still the club’s worst run since the 1900s, and this was at a time when Everton were often fighting relegation. Yet they also frequently played superbly against United and Newcastle, and routinely thrashed Arsenal and an improving Chelsea at home. They won on their first two visits to Highbury to face Wenger’s Arsenal. Against an excellent Villa side in 1995-96, live on Sky, they were 3-0 up inside eight minutes. They also pummelled United 2-0 in the return fixture that season, with Fowler scoring twice; but for Schmeichel, it would have been a humiliating scoreline. And there were the two 4-3 wins over Newcastle, the first of which will probably always be seen as the greatest Premier League match. Yet they also made a habit of losing at home to sides who would be relegated: Sheffield United in 1993-94, Ipswich in 1994-95, Barnsley in 1997-98. And they always lost to Coventry. “They were,” said the Guardian’s Scott Murray, “the set text on frustration.”

In those days you could afford to drop more points than now. The league was more competitive, and 80 points was almost always enough to win the title. But Liverpool still dropped too many silly points – not a huge amount, but just enough for it count come May. “We weren’t far away,” said Collymore, “but we weren’t close enough.”

“On our day we were as good as anybody but our day was not quite often enough,” said Evans. “We got caught out too many times believing we could attack any team and outscore them. It was my choice to go that way.”

Those extended bad spells are perhaps slightly overplayed. United went five games without victory in the winter of 1995-96, and Arsenal lost four out of six in the winter of 1997-98. But both went on to win the title because their hot spells were hotter than Liverpool’s. Arsenal won 10 in a row to win their first title under Wenger and two years earlier United won 13 of their last 15 to reel in Newcastle and keep ahead of Liverpool. Seven of those 15 matches ended 1-0, with Cantona scoring the winner in five of them. Cantona was already immortal at Old Trafford – the kung-fu kick confirmed that – but the way in which he won that title confirmed a relationship with the United fans so spiritual and enduring as to be without comparison in the history of English football.

The simple story of the 1995-96 is that United had a better defence than Liverpool and Newcastle. That is basically true, yet it is not quite as extreme a contrast as we think. Liverpool conceded fewer goals than anybody except Arsenal, and United were the top-scorers.

When United and Liverpool met in the FA Cup final at the end of the season, there was not the expectation of a classic; there was the assumption of one. Instead it turned into the New Year’s Eve of cup finals, with the hype in direct proportion to the anti-climax. Pound for pound, it might be the worst FA Cup final ever. Yet it was extremely memorable, for two reasons: the completion of Cantona’s redemption, a marvellous late winning goal, and Liverpool’s sartorial travesty. It was the White Suits Final.

“Never,” said Matteo, “has so much damage been done to a team’s reputation than by what we chose to wear.” Or rather what James chose for them to wear. He was modelling for Armani at the time and was asked by Barnes, the captain, to arrange blue suits. James came back with cream suits and said that was all they had. Even the weathermen were partially to blame; the erroneous perception that the FA Cup final was usually played in sunny weather led the person at Armani to choose something that they thought would look good in the sun.

Barnes let it drift and Liverpool turned up in white suits and sunglasses “looking like the Four Tops,” as Barnes put it. But, as he said three years later on the BBC’s Match of the Nineties, “if you do something like that, you’d better win”.

It is a recurring theme among the Liverpool players and staff at the time they were only nailed for their behaviour because they didn’t win. “They were horrible but it was just a bit of harmless fun,” said Evans. “No one would have bothered if we’d won the game.” Instead they become the defining symbol of Evans’s reign. The situation might have been even more farcical: the players wanted the management team of Evans and Ronnie Moran to wear them, an offer they sensibly declined. Some of the older players looked painfully self-conscious. Ian Rush, in particular, looked less comfortable than at any time since his year in Italy. To him, you suspect, it was just like wearing a white Armani suit.

“It was not white, it was cream, maybe even almond,” said James years later. “If there is an irritation, it is that the suit was more memorable than the final. Had we won the cup … we would have been the best dressed team to win the cup.”

The suits were not mentioned at all by the BBC studio panel before the game, which furthers the sense that criticism only came afterwards. That said, they were the talk of the United dressing-room before the match. “Our attitude was: Who the hell do they think they are, poncing around like John Travolta?” said Giggs in his autobiography. Cole’s first greeting to his friends in the Liverpool side was: “What the fuck are you boys wearing?”

Even Beckham had his say in his autobiography. “The Liverpool players were strolling round Wembley like it was their own front room. Some of them were wearing trainers,” he said, although it’s not easy to discern whether he was appalled as footballer or as a fashionista. The best appraisal probably comes from the endearingly loose tongue of David May. “We thought they looked like fucking knobs, absolutely ridiculous,” he said in Andy Mitten’s book Glory Glory! “They were there in their Armani suits and ours were from Burtons.”

To most it proved you are what you wear, and aptly summed up the gaudy immaturity of the Spice Boys. They were slaughtered in the press on the Monday after the final. “John Barnes and Stan Collymore wearing coloured boots; the unselected ponced up in cream suits; Neil Ruddock carefully adjusting dark shades – when Liverpool took the field at Wembley it was enough to have turned Bill Shankly and Bob Paisley a whiter shade of pale,” wrote Ken Jones in the Independent. “Times are a-changing, with football becoming as much show business as sport, but surely not enough to intrude upon the Liverpool ethos: nothing flash, and the priorities of touch, pass and calculated togetherness. Surely they, more than any other English club, would stoutly resist the more extravagant commercial blandishments.”

“A shower of narcissists,” was the description of Brian Reade in 44 Years with the Same Bird, and when they subsequently lost the match it hardened the perception of a team who – to reverse a phrase associated with United – were not better, just arrogant. “I can’t believe it was allowed to happen,” said Jamie Carragher in Men in White Suits. “It was a massive mistake and it gave the wrong impression, feeding a reputation that still follows all of those players around today.” Ferguson even referenced the suits in his team talk. “Keep playing the ball around their area,” he said, “because David James will probably be waving at Giorgio Armani up in the directors’ box.”

It is one of life’s greatest regrets that Roy Keane’s internal monologue was not available at the precise moment he saw what Liverpool were wearing. There had been signs that he was not entirely enamoured with the Liverpool team and their philosophy, most notably when, during a night out with Lee Sharpe, he bumped into a number of the Liverpool team. One by one, with regular recourse to a popular four-letter word, Keane drunkenly gave them a sneak preview of the devastating character assassination he would perform on Mick McCarthy in Saipan a few years later. On some level you suspect he was envious of their easy-going nature. The Liverpool players were to him what the “happy wanderer” was to Tony Soprano: “I see some guy walking down the street, you know, with a clear head. You know the type. He’s always fucking whistling like the happy fucking wanderer. I just want to go up to him and I just want to rip his throat open. I want to fucking grab him and pummel him right there for no reason. Why should I give a shit if a guy’s got a clear head? I should say ‘a salut’, good for you.”

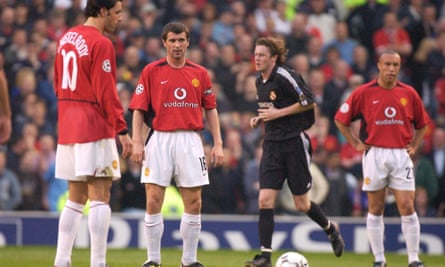

Keane certainly had respect for their ability, having chased plenty of shadows in the 2-2 at Old Trafford. “They were a useful team,” he said, “especially if they were allowed to play their passing game.” He did not, it’s fair to say, think they should be allowed to play their passing game. Tellingly, Keane missed most of the matches between 1994 and 1997 when Liverpool dominated United in midfield. United’s eventual ability not just to beat Liverpool but dominate them was inextricably linked to the emergence of Keane as the best defensive midfielder in the world. They were not quite ready to do that at Wembley, but Keane at least ensured Liverpool would not dominate them as they had done in the last five league games. He looked at Liverpool’s slick midfield and attack, considered all the talk that this was be a classic attacking match, and concluded: Nah, not on my watch.

Keane was playing a slightly different role than usual. Ferguson originally considered playing 3-5-2 to match Liverpool but after a meeting with Schmeichel, the back four, Keane and Cantona, he was dissuaded. Cantona then suggested sitting Keane in front of the back four in a 4-1-3-1-1. The result was a quite awesome performance. There has always been a simplistic perception of Keane as a licensed thug. He was reasonably decisive in the tackle, for sure, and on this day he harassed Liverpool to within an inch of their sanity, but an equal if not bigger strength was his forensic reading of games and higher state of concentration. For Keane football was like chess-boxing, placing equal, extreme demands on brain and brawn.

It was one of Keane’s finest performances, probably second only to his career-defining effort against Juventus three years later. He was aided by Ferguson’s decision to tuck Beckham and Giggs inside when United didn’t have the ball, and particularly by the diligence of his trusted lieutenant Butt, but really this was all about Keane. He got Fowler, McManaman, Collymore and Redknapp in an armlock.

“Neutrals said the 1996 Cup final was a bore,” sniffed Keane in his first autobiography. “Not if you were playing. It was grim all right, demanding every ounce of concentration, every last grasp of breath. My job was to anchor midfield, to deny Liverpool time and space, to break up their rhythm, basically to destroy any notions they might have had about passing us to defeat. There’s a lot of ground to cover at Wembley, but I covered it, got my tackles in, delivered the message: this is going to be hard work, boys, fucking hard work. Along with Nicky Butt I won the midfield battle. Nicky was a tough lad and an ideal partner for this kind of operation.”

Keane’s performance ensured Ferguson’s tactics worked. “We succumbed to United because they boxed us in,” said Barnes. It’s a classic United ploy when they are faced with three central midfielders. I spoke to Sir Alex Ferguson about it some time afterwards and he was aware going into that final that Liverpool often outplayed them, even though United often won.”

Fowler later said United were excessively negative. The video suggests he is confusing defensive excellence with defensive intent; United, in fact, started the game magnificently and could have been 3-0 after five minutes before the game settled down, and further down. “The match was crap,” said Giggs in his autobiography, “but we were the better team.”

Liverpool were probably having their best spell when, in the 86th minute, United won the game with a marvellous goal. Beckham’s corner was punched clear by James and deflected off the substitute Rush to the edge of the area, where Cantona backpedalled to hit a technically immaculate shot that swerved away from a phalanx of Liverpool defenders protecting the goal.

It was the completion of Cantona’s comeback and after the game Ferguson only wanted to talk about one man. Keane. When asked to praise Cantona, he did and then changed the conversation. “I thought Roy Keane was the best man on the park. Absolutely magnificent.” This was the day when the professional love-in between Keane and Ferguson went to another level. Keane returned the compliment in his autobiography. “The double of 1995-96 vindicated the manager. He had won something with ‘kids’.”

With hindsight, this was the moment the two teams really started to diverge. “If we had beaten them in the FA Cup final in 1996,” said Redknapp, “that would have given us the confidence to win the Premiership.” It was also, perhaps, the moment United took over from Liverpool with a kind of symbolic permanence. The two titles in 1993 and 1994 might feasibly have been isolated successes. This suggested United were here to stay; to compound Liverpool’s misery, the winning goal was unwittingly created by Rush, who scored so many FA Cup goals in Liverpool’s golden era and was one of the last men standing from that period. It was his last meaningful touch as a Liverpool player.

The 1996 Double was perhaps the most charming of all Ferguson’s triumphs at United. They achieved so much subsequently – and the Double became so commonplace – that it’s easy to forget just how big the Double Double was. They won it with kids and a returning idol, and they won it against Liverpool.

The club captain Bruce, who did not even make the bench for what would have been his last game for the club, gave an insight into his character by insisting that Cantona go up to collect the trophy. (Bruce’s reaction to such crushing disappointment was in contrast to that of Ruddock. When he was told on the Friday he would be left out, he told Evans to fuck off, then “cried like a baby” and drank the pain away.) As Cantona walked up the steps, he was spat on by a Liverpool fan. This time, there was no reaction.

Ruddock said Cantona gave him his shirt in sympathy, though when the shirt was later sold at auction – fetching £15,000 – the story had changed somewhat: the catalogue said Cantona had swapped with Barnes, who threw it on the dressing-room floor in disappointment after the game. Ruddock asked if he could keep it. Barnes let it drift.

Ruddock ripped arms off his Armani suit straight after the game. “A designer suit with no arms: that was about as close to a symbol of that Liverpool team as you are ever going to get,” said Collymore.

Liverpool had a party at the Emporium Nightclub – one of the many sponsors on their team coach – after the game. That became another stick with which to beat them, though all teams did that after a cup final, win or lose. A year earlier, after losing the FA Cup final to Everton, United had an all-nighter at the Royal Lancaster Hotel. “Funnily enough,” said Giggs, “that party was the best we’ve ever had.”

Rush noted that he “seemed to be taking defeat a lot worse than some of the younger lads around me.” Matteo, by contrast, said that, after the game, “the scene was one of total devastation” and Fowler says the party was “rather subdued”.

While all players had a party in such circumstances, Collymore did what other players do not: he slept with his manager’s daughter. It was the inevitable conclusion of nine months of flirting. What Collymore did not know during the act was that Evans was in the hotel room next door. It was an apt way to end a day full of symbolism.

Even after the United Double, the stock of Liverpool’s young players was still higher. Redknapp, Fowler and McManaman all made England’s Euro 96 squad; only the Neville brothers did so of the United youngsters. McManaman was included in the Uefa squad of the tournament, though Fowler made only a couple of substitute appearances because of the excellence of Alan Shearer and Sheringham. This was a golden age of English strikers and No10s: Venables had to choose between Shearer, Sheringham, Fowler, Ferdinand, Collymore, Cole, Ian Wright, Peter Beardsley, Nick Barmby, Matthew Le Tissier, Chris Sutton and a young Scholes, with Owen also emerging a year later.