Following the release of Gladiator, the New York Times said Russell Crowe “resurrected a soulful, often tragic masculinity not seen on American screens since the he-man martyr years of the 1970’s”. The revival was to be short-lived. While promoting a film of his own earlier this year, Crowe lamented the loss of the “archetypal Australian man”, the gruff, assertive figure who “appears stuck in his ways but is, in fact, quite an open person”.

Now it’s US actor Michael Douglas’s turn to worry about masculinity. Douglas, who followed his father, Kirk, into a decades-long career in Hollywood, said last week that there’s a crisis in the US film industry. Some actors in Hollywood are becoming too swept up in social media and their image, which is inhibiting their ability to be masculine. Douglas believes there aren’t enough Americans around like Chris Pratt and Channing Tatum.

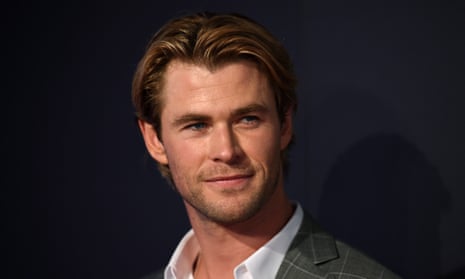

Instead, large-muscled, hairy-chested Australian actors are swooping in to steal all the proper roles, as American men languish in an “asexual or unisex area [of] sensitive young men”. Douglas doesn’t name any Australian actors, but might be referring to a kind of “Hemsworth effect”, given Chris Hemsworth’s recent multiple-film role as Marvel’s superhero Thor, and his brother Liam’s presence in Hollywood. (For what it’s worth, Chris also has a role in the upcoming female-led Ghostbusters reboot, as the receptionist.)

This is not recent. Hollywood has always been a global industry open to Australian imports. Errol Flynn, after all, became one of the most famous and desired men in the industry, a charming, swashbuckling, Robin Hood. What Douglas, and Crowe, seem to be commenting on is the breaking down of the old stereotype of masculinity.

As our own local film industry grew, we had various incarnations of the Bushman, a few Ned Kellys and countless shearers and farmers. Our most famous national film icons, Crocodile Dundee and The Man From Snowy River, perpetuated this myth, appealing to an international audience trying to understand the Australian way of life.

The rugged, emotionally unavailable battler is a stereotype that our local film industry has recently been trying to break down, in an attempt to express a wider range of male emotions. The image was lovingly spoofed in The Castle. Films like Romper Stomper and Animal Kingdom expose the dangers of a particularly insular type of persona against which men had to prove themselves, or face rejection. We’ve had director Ana Kokkinos bring a new type of character to the screen, with Head On (1998) and The Book of Revelation (2006). Now it’s Ruben Guthrie, Brendan Cowell’s reflective film that cuts through the celebration of Australia’s booze culture.

As traditional gender roles have changed over time, and the general expectation that men fit a particular mould has dissipated, there isn’t the same rigidity. It isn’t like the only roles in America are those that embody a typical masculinity. Diversity is a part of life, and it matters. It’s not that Australian masculinity has softened and our male actors are looking for an outlet. For many in the business, Hollywood is the ultimate destination, and it has been for years. Australian actors haven’t gone to Hollywood because it’s a space they can feel masculine. They’ve gone because that’s where they want to work.

Instead of there being a competition for the most masculine on-screen persona, we should approach actors with an appreciation for their work. Thinking about divisions like national identity isn’t helpful, either, because Australians, Brits, and actors from other nationalities aren’t intruders in Hollywood. They’ve helped to build it, bring it commendations, make it what it is. While the sullen, strong masculinity Crowe and Douglas are nostalgic for is a thing of the past, so is the idea of a contained national cinema; we’re much richer when we share.