Hong Kong, Hong Kong - People join the protest to the Chinese Liaison Office in Sai Wan, Hong Kong to mourn the death of Chinese Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo. People hold candle under heavy rain mourning the death of Liu Xiaobo and also demanding China government to release Lau's wife Liu Xia. PAimages/Chan Long Hei/Pacific Press via ZUMA Wire. All rights reserved.Liu Xiaobo’s death last week was a painful reminder of the dire state of personal freedoms in China. The dissident was imprisoned for nearly a decade. His crime: a view of a democratic China, a goal to be achieved peacefully. He died in custody, his dream yet to be realized. At 61, he suffered multiple organ failure allegedly caused by liver cancer. He had been denied permission to travel for medical treatment overseas.

Liu’s appeal for a more democratic China can be traced back to the Beijing 1989 protests. He joined the movement in Tiananmen Square, which resulted in a two-year jail sentence. But the government could never silence him. His calling to change the status quo remained as strong as ever as he continued to voice his concerns over the state of repression in the country. The regime tried to keep him at bay by detaining and sentencing him to 11 years in prison. Yet even there, his struggle was not forgotten. The Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded him the Peace Prize in 2010.

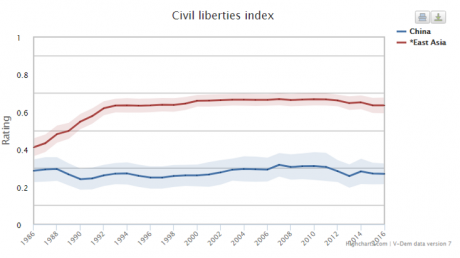

This time of mourning should give us pause to reflect on China’s protection of personal freedoms. Regrettably, the data confirms a bleak reality. A glimpse at the Varieties of Democracy Institute data below reveals that civil liberties in the country fare poorly when compared with the rest of the East Asia region. Most concerning, while this aspect of democracy mainly improved in the rest of the region between the mid-1980s and early 1990s, over the same period it deteriorated in China, and has remained the same ever since.

Freedom House provides a similar account. It gives China a freedom score of 6 out of 7 in civil liberties, 7 being “the least free”. Most alarming, over the past four years the administration intensified its crackdown on freedom of expression, chiefly online media as well as basic forms of association.

Indeed, since 2015 the country experienced a new wave of abrasive democratic restrictions including the imprisonment of numerous civil rights defenders who were tried for their political beliefs. Most notably, activist Zhang Haitao was subject to a stringent 19-year prison sentence for his critical remarks of the government. In a country where reports of custodial torture are widespread, the prospects to survive behind bars remain narrow.

This democratic dearth stands in contrast to the region and the rest of the world. In the last century most countries became or remained democratic, and estimates from the 2017 Economist Democracy Index now label 109 countries as “democracies” (either full, flawed or hybrid). China stands at a shameful 138 (among 167 countries in the total ranking), right below Yemen.

Alas, other countries have also experienced democratic reversal since 2006. Estimates from the Bertelsmann Stiftung indicate that 28 countries suffered democratic decline in the period 2006–2016. My research on democratic backsliding (to be featured later this year as part of International IDEA’s forthcoming publication on the Global State of Democracy) analyses these trends.

After one year of data collection, our findings show worrying authoritarian signs in relation to some countries with a once decent democratic track record, or a steady path towards democratic consolidation. Venezuela’s growing political repression, Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s targeting of intellectuals in Hungary, and the extension of the presidential term limit in Congo-Brazzaville illustrate that, after taking one step towards democracy, a country can still take two steps backwards.

Even in countries where democracy is most consolidated, maintaining it takes effort. Great challenges remain. Growing public distrust in political parties is a case in point: the World Values Survey and Transparency International indicate that, by and large, people regard political parties as the most corrupt organizations in their countries. This is even the case in places long considered beacons of democracy like the United States, Argentina and South Korea.

In this mixed environment of freedoms and repression, the common anchor that may ground our hopes for a more democratic future is the relentless work of activists and civil leaders, such as in Venezuela, Hungary and the Congo-Brazzaville where democratic regression has yielded a chain of protests.

Even in some of the most unhospitable environments for dissent, citizens with a view similar to Liu Xiaobo’s are still championing peaceful democratic reform. Liu’s tragic passing has already prompted renewed calls for democratic change in Hong Kong. A lot can still be done.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.