The psychology of cities goes to the very heart of what is vital to explore if we are to improve city living and the urban experience. How we process a city is, I believe, primarily emotional. Though place can be mapped, named, politicised and controlled, the reality of urban spaces and places exists in our mind, in our experience.

In this way, a single city is different for every person who lives in or visits it: there is no one universally accepted truth of each place. The sheer amount of physical spaces, places, activities, people, processes and relationships in a city makes it very unlikely that any two urban lives are the same.

A writer called Jonathan Raban wrote a book, Soft City, centred on this emotionally shaped urban life:

“The city as we imagine it, the soft city of illusion, myth, aspiration, nightmare, is as real, maybe more real, than the hard city one can locate on maps in statistics, in monographs on urban sociology and demography and architecture.” (Jonathan Raban, Soft City)

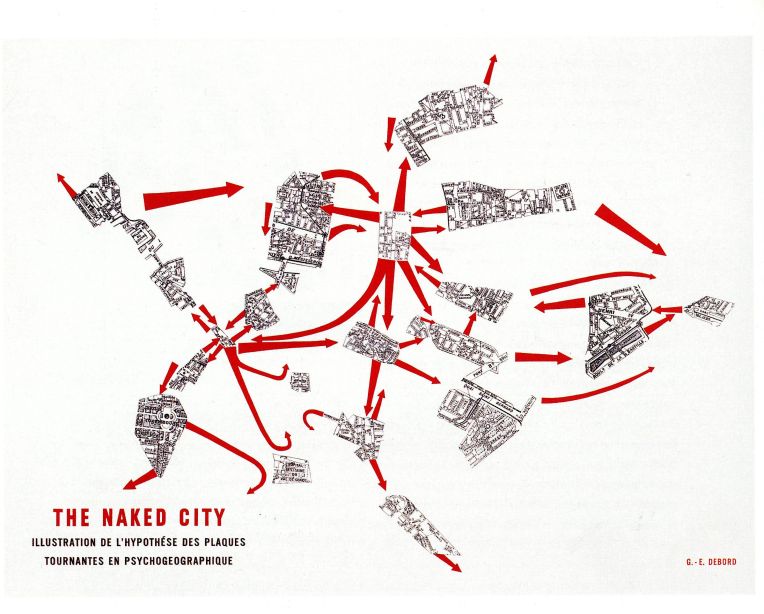

I don’t believe we exist in a constant state of nightmare or illusion – but I appreciate Raban’s point that emotional experience shapes spatial realities rather than factual knowledge. It was this idea that inspired, or drove, the Psychogeographers – a group borne from the Situationist movement in the mid-20th century (and about which I won’t write an essay here). Though psychogeography has evolved and taken on many forms since then, the core idea was to draw attention to how the city and the places within it affect us emotionally and what personal geographies we create for ourselves out of them.

How we see the city and its organisation is defined by the routes we take through it, the memories we associate with certain places and the myths we identify with unexplored areas; realities wholly unrepresented by traditional maps. As our cities are experienced through our mental comprehension and experience, so they will always be malleable – or soft – to our distortion, subjectivities and associations. Focusing on personal geographies is often a way of coping with the immense amount of information a city offers us.