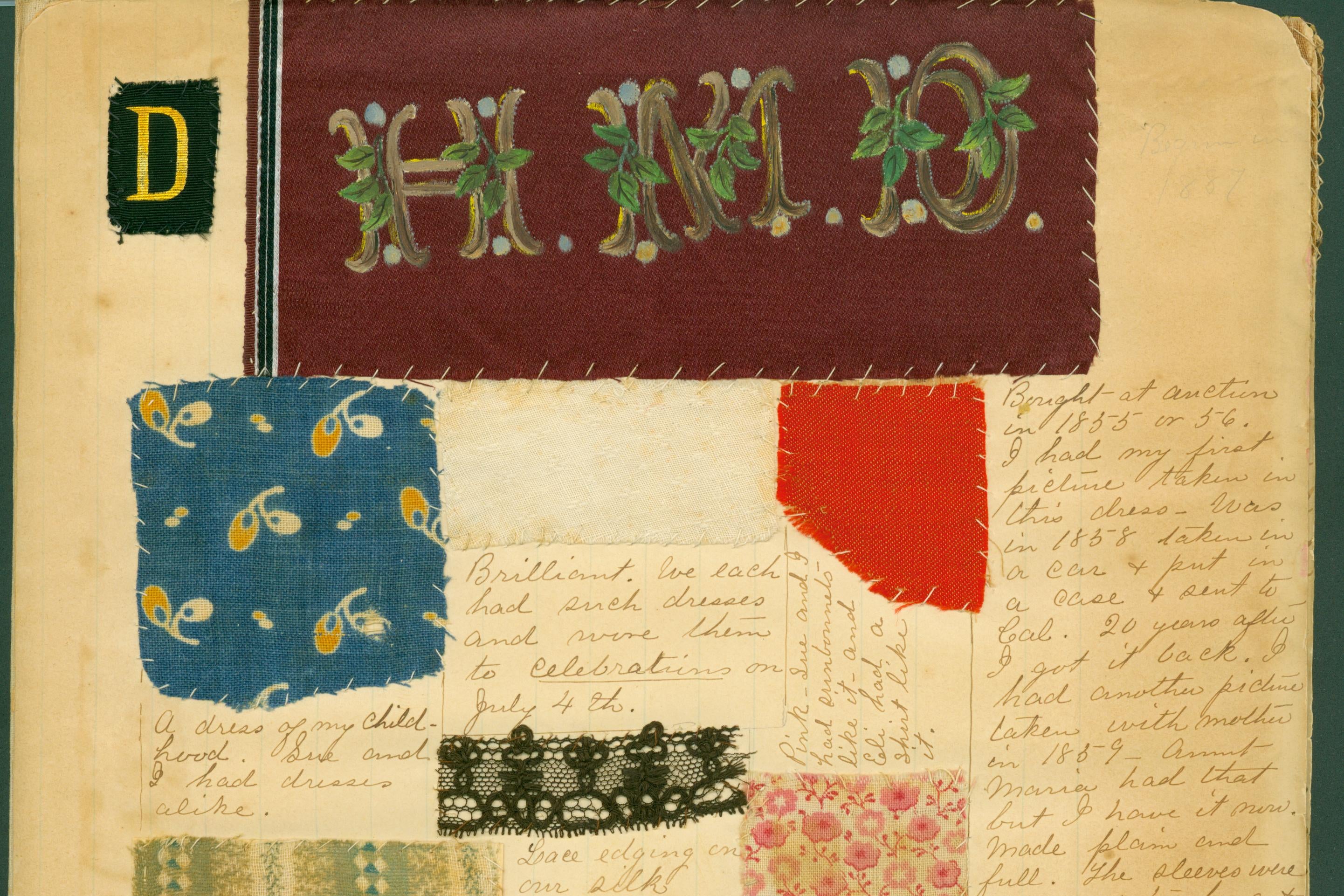

Hannah Ditzler Alspaugh started work on this detailed fabric scrapbook in 1887, and ended it in 1903, with a bit of silk from her wedding dress. Alspaugh annotated each sample with details about a garment’s making, remaking, circumstances of use, and eventual demise; some of the samples date back to the Civil War. The book, created by a woman who had a beautiful mania for documentation, is a singular artifact of the culture of 19th century domestic dress-making. It chronicles people’s relationship to clothing at a time when most who, like Alspaugh, weren’t super-wealthy had no choice but to sew their own.

“Hannah’s notes are extremely detailed and extremely emotional,” said Dina Kalman Spoerl, exhibits team leader at Naper Settlement in Naperville, Illinois, whose article in the American Historical Association’s Perspectives on History magazine introduced me to this document in her organization’s collection.* “Everything has a label on it. Everything has at least a line about when she got it, how she wore it, what she did with it, during the course of its life with her.”

Alspaugh, whose farmer father moved to Naperville from Pennsylvania, was a teacher, artist, and librarian. She remained unmarried for most of her life, before finally wedding a cousin in her middle age. Though other women of the time also created fabric scrapbooks, Alspaugh’s has much more detail than most; at 42 pages, it describes hundreds of samples.

Left-hand column, notation under two stacked samples of cream-colored fabric with blue and green patterns: “Worn in childhood. The blue was only a skirt and used to wear a white waist with it. The green had a waist and I tried so hard to have it cut low in the neck – finally mother cut it out only enough to always provoke me. I wanted the shoulders cut like all the other girls.”

Alspaugh’s mother’s presence runs through this book, showing how the creation of clothes before the wide availability of store-bought garments demanded work from all the women in a family. This particular memory destroys any sepia-toned vision of domestic industriousness and family togetherness the sentence before this one might evoke. Imagine making a garment for your begging teenage daughter, and fighting over necklines all the way!

Middle column, notation to the side of yellow-and-white plaid scrap: “Yellow – Sue [her sister] and I had dresses alike. She wore hers and was walking on Hyers picket fence one Sunday as another was coming home from church. She was afraid of a good scolding so she jumped but her dress caught on the fence and she fell besides tearing her dress very badly.”

Ditzler often annotated a fabric scrap with the date that the dress made from it was ripped.

With clothes much scarcer than today, a tear resulted not in the garment being tossed, but in a new round of work for the seamstresses in the family. Naturally, then, such events made an impression.

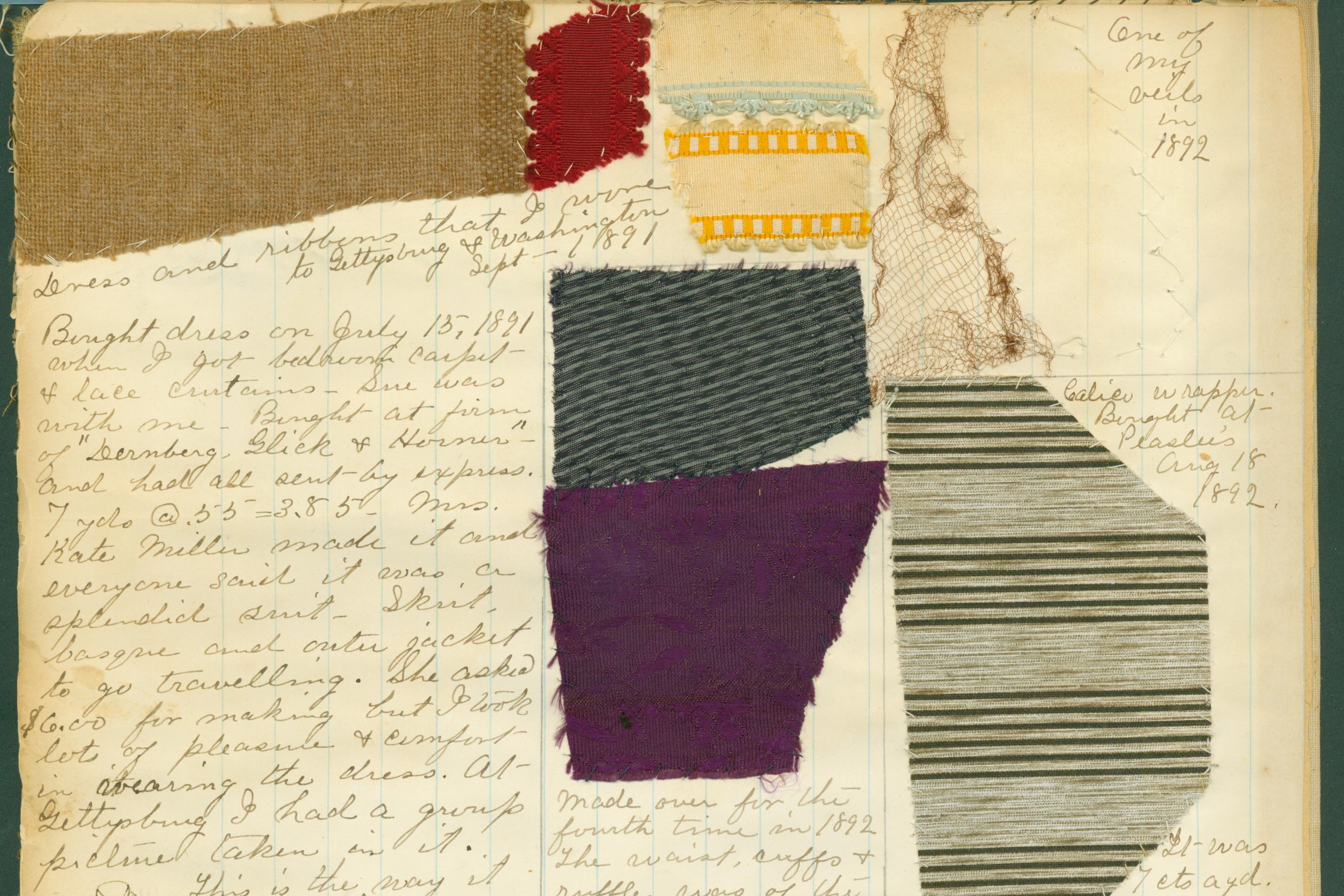

Middle column, notation under black silk scrap: “Reached the height of bliss when I owned a black silk dress. Bought at Schlessinger & Myers – Chicago in fall of 1884 for $1.00 a yd. Sue was with me and I got 15 yds – so I paid $15.00 all in gold – which I got this way – 5.00 exchanged bill with father for a new gold piece that Rev. Dixon gave him – 5.00 mother gave me for a Christmas present – 5.00 I earned making a portrait. So I hoarded my gold carefully till I bought this in spring of 1885. Mrs. Martin made it for $6.00 – box pleating in skirt – pointed drapery basque with fullness in back – wore first at Art Reception in College & Commencement in June 1885. Wore in Iowa in 1885. In 1894 put in big puffs on sleeves & wore that summer & winter. Fall of 1897 ripped and washed it – made over new for the fifth time & trimmed with jet – bolero front – wore first time over to Emma Bristols – She said it was pretty. More next page.”

Alspaugh, a single woman for most of her life, was particularly proud of providing herself with such a fancy dress. (The prices noted next to other swatches are much lower—about half or a third the dollar-a-yard this silk cost, and sometimes, as with calico, much less.) Alspaugh often recorded compliments people gave her on her clothes, decades after those kind words were doled out. Several times, too, she notes instances when she bought a light-colored type of fabric, and others asked whether it was intended for her wedding dress. (Until 1903, it wasn’t.)

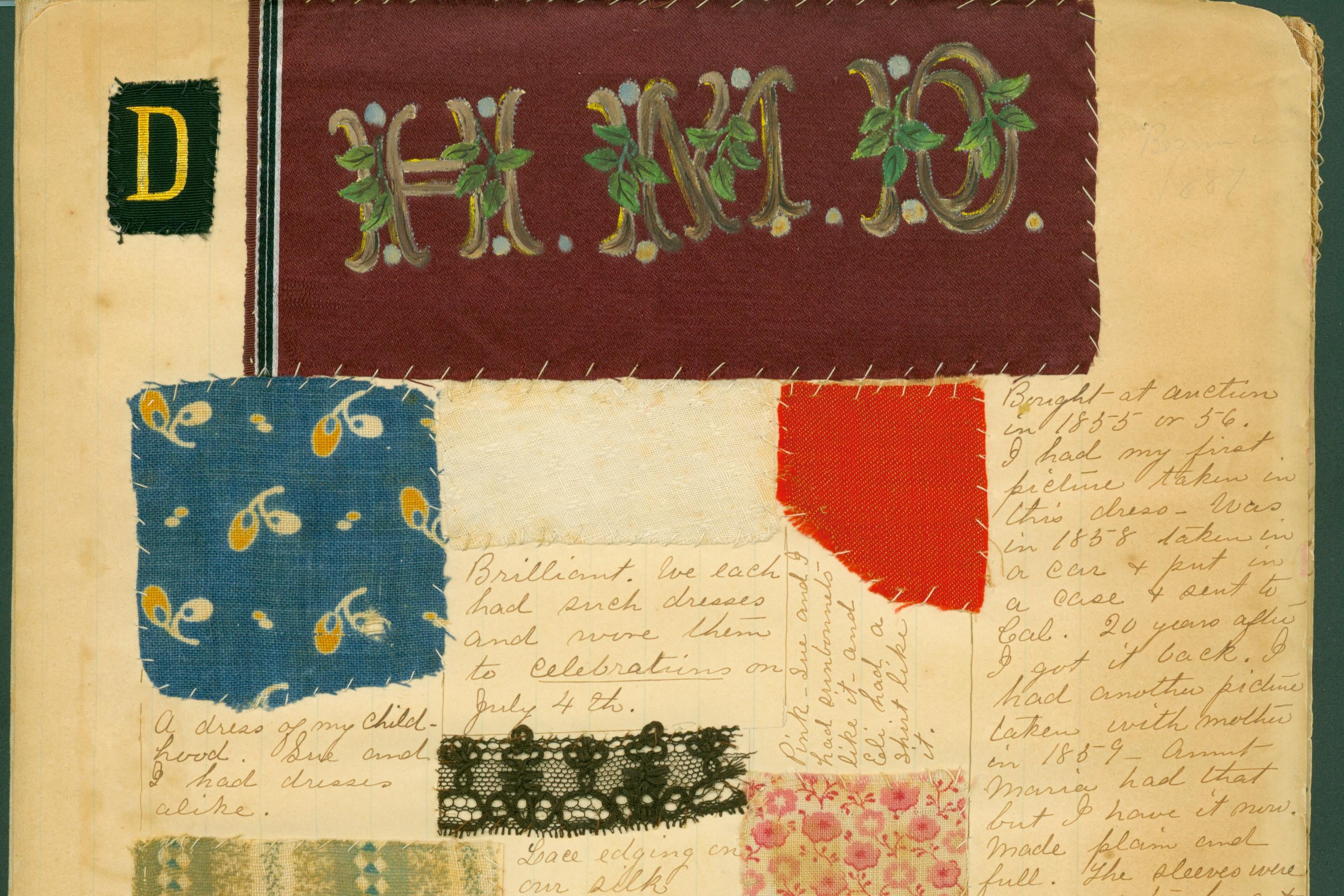

Middle column, notation under brown scrap: “Brown dress & velvet trimming. Bought in Chicago at for 33 cts a yard. 5 yds velvet ribbon at 10 cts. Made this dress alone & was about 6 weeks doing it with other work. Plain full skirt with velvet panels like this [drawing of skirt and to the right drawing of bodice] collar, front and cuffs of velvet waist plaited and sort of girdle of brown. All told me it looked nice but oh, what moans & groans while making it! In 1893 I ripped it & Mrs. Miller made me a lovely suit of it. The velvet around bottom of skirt & belt, cuffs & collar. My Worlds Fair dress for I wore it most every time.”

With Naperville being about thirty miles from Chicago, Alspaugh was able to visit the 1893 World’s Fair often. The grand exhibition pops up a few times in the scrapbook’s pages, as she records the types of dresses women tended to wear on its grounds.

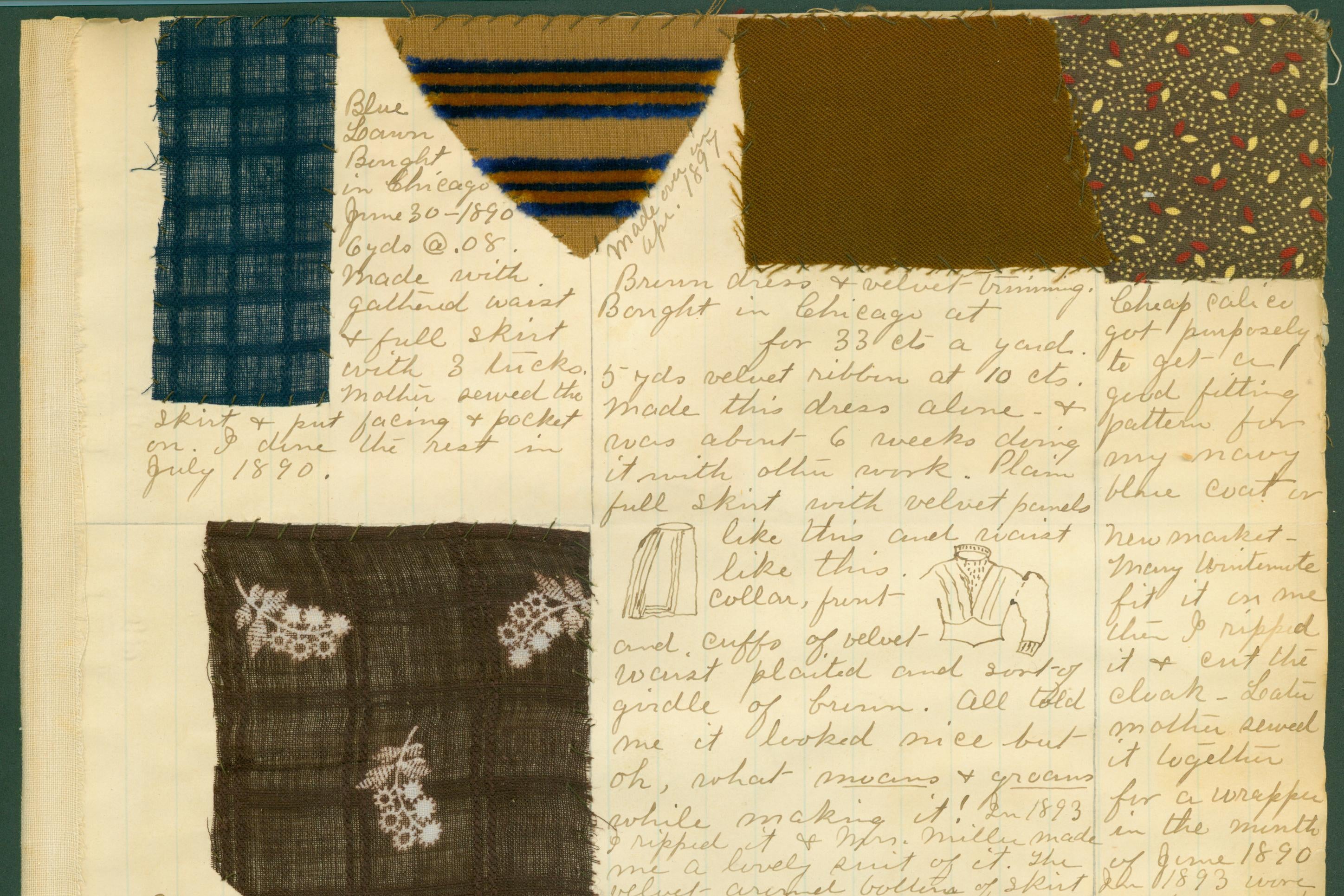

Right-hand column, notation top of and underneath the scrap with horizontal black stripes: “Calico wrapper. Bought at Peasler’s Aug 18 1892. It was 7 cts a yd. Mother sewed the facing on as she was recovering from illness. Worn out in 1895.”

Who bought the fabric for a garment, and who made it for the person who wore it, were details Alspaugh never neglected to include, as in this note about her mother’s service in sewing a wrapper while recuperating from sickness. On several other pages of the scrapbook, Alspaugh collects scraps of the dresses and aprons her mother wore, including one annotated “the last dress that father bought for her,” and an apron scrap with the note “this blue is the one she wore last.”

On her “mother’s dresses” pages, Alspaugh’s notes show how garments embodied family care; often, one family member bought her mother the fabric for a gift, and another made it into clothing. “Mother’s last dress,” she notes next to one such scrap. “I bought it for her in Chicago in 1901. Sue and I made it for her that winter. She was so slight and it fit her well, so she looked like a doll and it was so becoming. The last time Eli [Hannah’s brother] was over when she was up was Jan 11 1903 and she wore it that day for the last time.”

Correction, June 2, 2021: This post originally misidentified Perspectives in History as a blog. It is a magazine.