MARIO GIACOMELLI: BEYOND TIME

REVIEWS

The talents of some artists so precisely mesh with their times that their work becomes the sign and summary of an era: take, for example, Walker Evans's Depression-era photographs, that cool, orderly, and dignified document of abject poverty. Other artists skirt their period or culture to court their personal gods or demons; Mario Giacomelli was one of these.

Italian postwar photography was largely ignored by the rest of the world until recently, and almost entirely eclipsed by the popularity of neorealist films. But Italians were hungry for images after the war— in 1951, only 13 percent of reading-age citizens were literate—and photographers supplied them liberally. Until the upheavals of the 1960s, the vast majority of those images were “straight photographs,” dedicated to what one critic called “that pressing reality which is there for all to see.” Giacomelli was neither a realist nor a neorealist but more original and more daring than a phalanx of good reporters—and for a long while the only Italian photographer

with an international reputation. A 150-photograph retrospective at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography last spring pounded home his tough poetry, which churns the mind still.

An amateur—he worked as a typographer all his life—Giacomelli sacrificed all the rules to the service of expression. His ceaseless experiments did link him to his times; he began as a painter, when Italian painters were embracing a new freedom in hopes of finding a place in the modern world. Giacomelli played endless games with perception and wreaked havoc on his prints, overexposing and overdeveloping, using outdated film, bleaching, montaging, smudging with his fingers. He manipulated the landscape itself.

As early as 1955 (he began photographing in 1953), when harvests were over he would ask farmers to plow fields in patterns that interested him. Alistair Crawford, who knew Giacomelli and wrote a book about him in 2001, considers him an important forerunner of Land Art.

Giacomelli’s vision was indentured to death, and the dire notes sounded by that fierce master of all life ring powerfully through his images. When he was nine, his father died. To support the family, his mother washed clothes for an old people’s home, taking her son to work with her. Later, he took harrowing pictures of people in the home. He said: “What I was trying to show, rather than what I saw, was what was within me: my fear of getting old—not of dying—and my disgust at the price one has to pay for one’s life." He was quite content to shock—and he did. Italians had little interest in “art" photography and many found his offensive.

His landscapes, too, speak of the unbreakable union of life and death. Seldom have landscapes, except in woodcut, been so determinedly linear, caustic, and patterned, with ink-dark creases cutting in one direction and the washy strokes of adjacent fields in others until all tilt unsteadily. The only human sign might be a puny house, perched on a jumble of planes. The land is furrowed like the wrinkles on old faces, for the earth too is old and dying.

“In my earth photos I try to kill nature," Giacomelli said, “to take away the life it has been given—by I know not whom—and that has been destroyed by man’s activity, in order to give it a new life, to re-create it according to my own criteria and my vision of the world. Nature is a mirror in which I am reflected, because by rescuing this land from its sad devastation, I am in fact trying to save myself from my own inner sadness."

At times he dallied with abstraction, anchoring great swaths of darkness or featureless forms by a few traces of planted rows or two-dimensional trees. Variable focus skews the view further.

The little boy in the middle distance in a well-known 1957 picture from Scanno is as distinct as a specimen under a microscope, while the two old women in motion up front tremble into blur: old age exiting while youth moves toward it. In a photograph taken in the old people’s home, four old women, irregular silhouettes, move away from us, while thrusting into our space is the gray and blurred face of a woman with open mouth and closed eyes. If the four in back are moving slowly toward death, this woman is on the verge of keeping her appointment.

Photography beyond photography—Giacomelli plucked a strange new reality from a reconfigured universe. This is a world gone awry; either it is unstable or we are. Rational understanding is no longer possible; all that is left is feeling. Giacomelli said he tried to photograph thoughts, like others (consider Alfred Stieglitz’s Equivalents) who photographed the exterior world in order to convey an interior one.

Black-and-white film is an apt medium for so dark a view of the world. The pictures of priests romping in the snow, one of his more lighthearted essays, is printed at such high contrast that the black shapes of their cassocks dance in staccato intervals over a flat white page like capital letters of some fanciful alphabet typed on white paper. The Catholic church was offended by these images. (Giacomelli had brought the seminarians cigars and photographed them smoking—not an altogether saintly activity.) As for his extended look at Scanno—part of the old and unchanged Italy—the women there were already silhouettes in black, the houses white in the sun. Giacomelli lived all his life in a small town and photographed other such towns. Other photographers did too, to foster an inclusive sense of nationalism as the country was being reconstructed. But Giacomelli’s pursuit remained irrevocably locked in his mind and heart; a caption in Tokyo said that, feeling left out of his time, he identified with places that had been left behind as the country modernized.

Left out of or ahead of—it does not matter. What matters is a brutal poetry, an art wrested from fear and death, that ignores time and lives on, bursting with passion still.©

Vicki Goldberg

Mario Giacomelli was presented at the Metropolitan Museum of Photography, Tokyo, March 15-May 6, 2008.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Portfolio

PortfolioRichard Misrach Untitled

Winter 2008 -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessOn The Edge Of Clear Meanin

Winter 2008 By David Levi Strauss -

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledDisappearing Giants

Winter 2008 By Michael "Nick" Nichols -

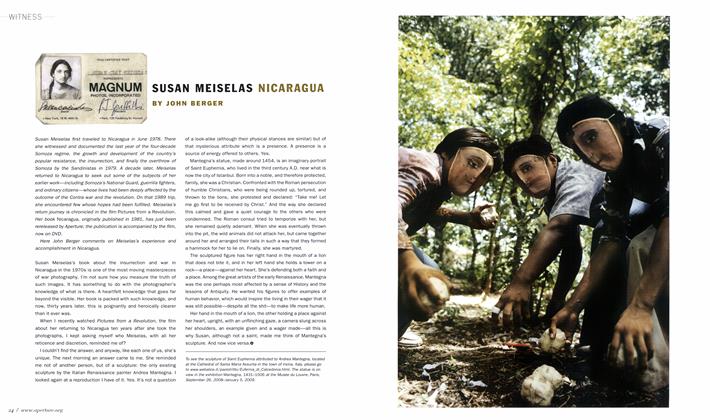

Witness

WitnessSusan Meiselas Nicaragua

Winter 2008 By John Berger -

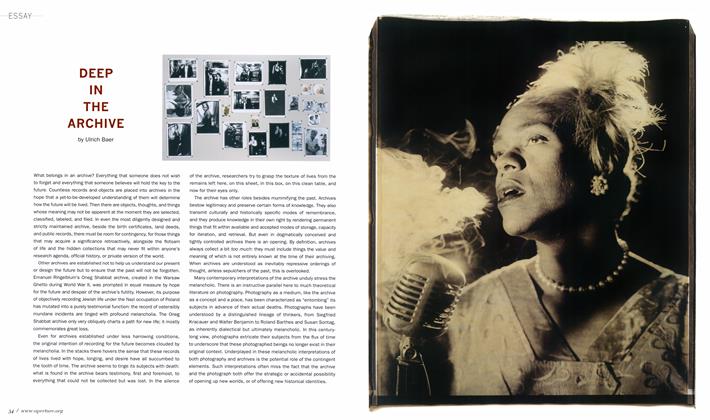

Essay

EssayDeep In The Archive

Winter 2008 By Ulrich Baer -

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaThe Author As Photographer Early Soviet Writers And The Camera

Winter 2008 By Erika Wolf

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Vicki Goldberg

-

People And Ideas

People And IdeasLee Friedlander, Dispassionate Voyeur

Fall 1991 By Vicki Goldberg -

Reviews

ReviewsFotofest 2004, "Water"

Winter 2004 By Vicki Goldberg -

Reviews

ReviewsEd Ruscha And Photography

Summer 2005 By Vicki Goldberg -

Reviews

ReviewsFirst Seen: Photographs Of The World's Peoples

Fall 2005 By Vicki Goldberg -

Reviews

ReviewsThe Gaze Of Desire

Winter 2005 By Vicki Goldberg -

Reviews

ReviewsLeon Levinstein

Summer 2011 By Vicki Goldberg

Reviews

-

Reviews

ReviewsMitch Epstein: American Work

Fall 2008 By Aaron Schuman -

Reviews

ReviewsRaymond Depardon Silence Rompu

Spring 2000 By Diana C. Stoll -

Reviews

ReviewsThe Body At Risk: Photography Of Disorder, Illness, And Healing

Summer 2006 By Fred Ritchin -

Reviews

ReviewsPhotodimensional

Winter 2009 By James Yood -

Reviews

ReviewsPoints Of View: Capturing The 19th Century In Photographs

Fall 2010 By Jason Oddy -

Reviews

ReviewsInternational Photographic Exposition

Winter 1953 By M.W.