Approach Considerations

Patients may not present to the orthopedist with mallet finger for weeks or even months, perhaps having received no treatment or ineffective treatment. Bony injuries heal within weeks; thus, an old bony injury without functional deficit is best left untreated.

A tendinous injury generally can be improved by extension splinting up to 6 months from the time of injury. The period of splinting for such an old injury is extended because the area becomes less inflamed as time passes. Therefore, fibroplasia and wound contraction occur more slowly and less completely.

Attempted open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of a mallet injury, either tendinous or bony, often results in a stiff, infected, or painful finger. In most instances, therefore, the surgeon should resist the urge to treat mallet finger surgically. [8] However, some indications for surgical reduction, such as volar subluxation of the distal phalanx, do exist.

Splinting

Mallet injuries, whether bony or tendinous, should be addressed with closed treatment. This injured area is constrained tightly by adjacent unpadded skin dorsally, a tightly constrained hinge joint volarly, and the germinal matrix of the nail distally. Splinting of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint in full extension allows healing of the injured structure and restoration of excellent function and appearance. (See the images below.) [9]

Skin-tight plaster cast can effectively hold distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint extended and proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP) flexed when mallet deformity is accompanied by hyperextensible PIP. Not immobilizing PIP in partial flexion risks development of swan-neck deformity.

Skin-tight plaster cast can effectively hold distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint extended and proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP) flexed when mallet deformity is accompanied by hyperextensible PIP. Not immobilizing PIP in partial flexion risks development of swan-neck deformity.

Patient education and compliance are keys to good results. Once extension splinting has been initiated, it should be maintained without even a momentary lapse for the prescribed treatment period. Tendinous injuries require 6-8 weeks of splinting, [10] and bony injuries require 4-5 weeks. [11]

The time that is spent educating the patient regarding the necessity for nonstop protection in extension, as well as in techniques for maintaining joint extension (even when cleaning the finger and changing the splint), will be rewarded with favorable results.

The DIP joint should be immobilized in full extension so that the finger is straight. Sustained hyperextension of the joint, however, may cause ischemia in the skin over the dorsum of the joint and contribute to the development of pressure injuries, which are occasionally observed as a result of tight splinting. (See the image below.)

Pressure injury can result from splint that is applied too tightly, especially if joint is maintained in hyperextended position rather than position of neutral extension.

Pressure injury can result from splint that is applied too tightly, especially if joint is maintained in hyperextended position rather than position of neutral extension.

Various means are available for holding the DIP joint in extension. Splinting can be isolated to the distal joint if the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint is not lax and does not hyperextend. Splinting the PIP joint in partial flexion for the first half of treatment is appropriate if the untreated finger assumes a swan-neck posture.

Small strips of aluminum with foam-rubber backing are commonly used in splinting. The foam backing should be of the closed-pore variety so that the foam does not absorb moisture. The open-pore form retains water in its interstices and harbors various microorganisms that hamper proper hygiene. Closed-pore foam aluminum strips are available from various orthopedic supply houses.

The aluminum strip can be applied either dorsally or volarly. Applied dorsally, the aluminum strip requires two strips of tape—one around the midportion of the middle phalanx and one around the midportion of the distal phalanx—for the splint to achieve three-point fixation and maintain the distal joint in an extended position. Dorsal splinting allows the digital pulp to be partially exposed for keyboarding and other daily activities. In addition, dorsal splints are more effective at maintaining the joint in full extension. (See the image below.)

Volar splinting, however, requires only one band of tape around the finger, at the level of the distal joint, to achieve three-point fixation; thus, the volar splint is slightly easier to apply and maintain. The aluminum strip, however, precludes any tactile feedback from the digital pulp for light activities.

Other rigid materials can be used for makeshift splints. A large paper clip can be padded with adhesive tape and then used as a splint. Also, some patients have improvised temporary splints with plastic disposable spoons or sections of wooden ice-cream sticks.

Premolded plastic splints are available commercially. However, they often do not fit the finger closely enough to maintain the joint in full extension. These splints have the added disadvantages of entirely covering and blinding the pulp from tactile sensation and preventing evaporation of moisture from the enclosed skin.

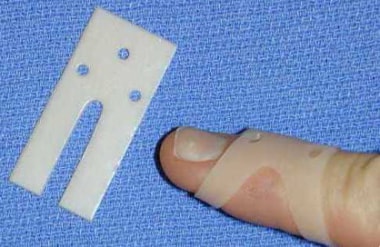

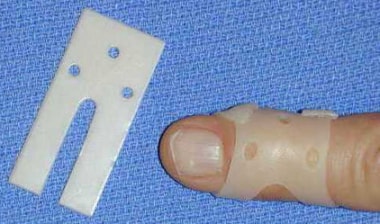

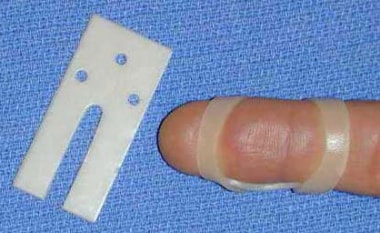

Having witnessed the shortcomings of the various splints, as noted above, the author devised a simple custom-molded plastic splint, as shown in the images below. This splint leaves the pulp relatively exposed for functional activities, adheres closely to the contour of the digit without the need for tape, and is of sufficiently low profile to allow for evaporation of moisture from between the splint and the skin. Blanks can be made from various thermoplastic materials that are routinely used by hand therapists or can be purchased commercially. [12]

The technique for applying this splint is demonstrated in the video below. (Contact George Tiemann & Co [25 Plant Ave, Hauppauge, NY, 11788; phone: 800-843-6266] to request more information or to purchase the Meals Custom Malleable Mallet Mender splint.)

Regardless of the splinting method used, patients should have a follow-up appointment 1 week following the initiation of splinting to ensure that the joint is being properly maintained in extension and will continue to be. An adjustment in splint size may be necessary if any surrounding edema has subsided.

Most athletes with mallet finger are able to participate in their sport during treatment. Additional padding and support of the affected finger may be appropriate for play in contact sports. Throwing athletes who injure their dominant hand may initially miss practice and playing time.

At the end of treatment, the DIP joint should be stiff in full extension. Full-time splinting in extension for an additional 2-4 weeks is advised if an extensor lag is noted. If no extension lag is present and strength against resistance can be demonstrated, the patient should begin a slow weaning of the splint over the next 1-2 weeks. At that point, the splint should be used for 2-4 more weeks at night and with activities that put the joint at risk. The patient may then resume full activity. Specific finger exercises to regain flexion are very rarely required.

Surgical Reduction

Concerns and indications

When a large bony fragment is observed, the surgeon instinctively wants to reconstruct the articular surface anatomically. It must be kept in mind, however, that this is a nonweightbearing joint, and articular incongruity, which would not be tolerated in the ankle or knee, is well tolerated in the DIP joint. This joint has been demonstrated to remodel beautifully over time, even in the presence of volar subluxation of the distal phalanx.

Moreover, late osteoarthritis at the DIP joint of an untreated mallet finger or a mallet finger that is treated without anatomic reduction of the fracture is rare, if not nonexistent. Thus, the risk of poor outcome from ill-advised open treatment far outweighs any risk of early dysfunction or late arthritis from splint treatment.

The appropriate indications for surgical fixation of mallet fractures, which techniques to use, and the accuracy of outcome measures are frequently debated. [13, 2, 14] Most authors agree that mallet fractures that are associated with volar subluxation of the distal phalanx should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon for fixation.

Referral should also be considered for cases in which there are large or displaced avulsion fragments that involve more than 30-40% of the joint surface. [13] Surgical fixation of a mallet fracture of the thumb is sometimes recommended because of the greater extrinsic displacing forces across the interphalangeal (IP) joint.

Techniques

Many surgeons prefer operative treatment of mallet injuries that are accompanied by volar subluxation of the distal phalanx. The belief is that the restoration of joint alignment and the balance between flexor and extensor forces is needed to obtain an adequate functional result in these patients. In general, the joint is reduced, and a transarticular Kirschner wire (K-wire) is placed. If the fracture fragment cannot be held in reasonably close approximation to its insertion site, it may be stabilized with another K-wire or with the pull-out suture technique. [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 13, 21, 11]

Occasionally, certain patients (eg, surgeons or dentists) may be unable to wear splints for the required 6-8 weeks for vocational reasons. With a digital block, a 0.035-in. K-wire can be inserted across the joint to serve as a temporary internal splint. Although the wire may help to maintain the reduction of a bony fragment, its primary purpose is to maintain extension of the joint. It can be difficult to get a K-wire to engage in the distal phalangeal tuft for a retrograde pinning.

Another option is to insert an oblique antegrade K-wire by starting at the midportion of the middle phalanx and placing the K-wire obliquely into the main body of the distal phalanx. By starting on the ulnar side of the digit, the wire can be clipped off just below the surface of the skin. The K-wire stabilization should be protected with an external splint when patients are not engaged in critical portions of their occupation. The K-wire can be retrieved and extracted with local anesthesia at the end of treatment.

On the basis of results in 9 patients with mallet fracture in whom extension block pinning had failed, Lee et al concluded that tension-wire fixation can be an effective second-line treatment in such cases. [22]

A study by Wang et al indicated that when splinting fails to achieve adequate resolution of tendinous mallet finger, a tendon-bone graft can be an effective alternative treatment. In 28 patients for whom splinting had failed, grafts were taken from the extensor carpi radialis brevis and the third metacarpal base. [23]

Complications

The most bothersome complication from closed management of a mallet finger is a dorsal pressure injury over the DIP joint. This results from excessive pressure of the splint or tape at that site and is probably potentiated by a hyperextension posture of the joint (see the image below). Treatment of mallet finger does not represent an instance in which one can assume that if extension is good, hyperextension is better. Notice, in fact, that dorsally over the DIP joint, the skin blanches when the joint is held in a hyperextended position. Prefabricated orthoses appear to have a higher rate of skin complications than custom-made orthoses do. [24]

Pressure injury can result from splint that is applied too tightly, especially if joint is maintained in hyperextended position rather than position of neutral extension.

Pressure injury can result from splint that is applied too tightly, especially if joint is maintained in hyperextended position rather than position of neutral extension.

Complications from open surgical management abound. Often, the small bony fragment is more comminuted than it appears on a radiograph, or it becomes comminuted during the effort at anatomic reduction and internal fixation. Mobilization of the fragment in an effort to obtain an anatomic reduction can further devitalize the fragment, leading to a risk of avascular necrosis. Infection, stiffness in extension, nail-bed damage, and chronic tenderness are other well-known problems of open treatment.

-

Despite active extension effort, distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint of index finger rests in flexion, as is characteristic of mallet finger.

-

Typical mallet finger deformity.

-

Large dorsal-lip avulsion fracture from distal phalanx: bony mallet injury.

-

Mallet fracture with volar subluxation of distal phalanx.

-

Stable mallet fracture involving 40% of joint surface.

-

Dorsal aluminum foam splint for treatment of mallet finger.

-

Stack splints are widely used for treatment of mallet finger.

-

Molded plastic stack splint for treatment of mallet finger.

-

Skin-tight plaster cast can effectively hold distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint extended and proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP) flexed when mallet deformity is accompanied by hyperextensible PIP. Not immobilizing PIP in partial flexion risks development of swan-neck deformity.

-

Pressure injury can result from splint that is applied too tightly, especially if joint is maintained in hyperextended position rather than position of neutral extension.

-

Thermoplastic blank for custom-molded mallet finger splint; oblique view of molded splint in place.

-

Dorsal view of custom-molded thermoplastic splint in place.

-

Volar view of thermoplastic splint in place.

-

Application of thermoplastic splint.